Openingswoord expositie Mowaffk al-Sawad – موفق السواد

Openingswoord expositie Mowaffk al-Sawad “Het Gewiste”, Gallery Out in the Field, Amsterdam, 13 januari, 2019

موفق السواد

Mowaffk al-Sawad komt uit Irak, maar is al geruime tijd actief in Nederland, als dichter, schrijver en voor deze gelegenheid het meest relevant, ook als beeldend kunstenaar. Het meest bekend is hij geworden van zijn brievenroman ‘Stemmen onder de zon’ (Uitgeverij de Passage, Groningen, 2002). Verder heeft is zijn poëtische werk in verschillende dichtbundels verschenen. Zo lang hij actief is geweest als dichter heeft hij ook geschilderd, al is het pas sinds kort dat hij met dit werk naar buiten treedt.

Mowaffk werd in 1971 geboren in Basra, de grootste stad van zuid Irak, waar de Eufraat en de Tigris samenvloeien en uitmonden in de Perzische golf. Op zijn negentiende, toen hij net was begonnen aan zijn studie theaterwetenschappen aan de universiteit van Basra, annexeerde het Iraakse leger Koeweit, gevolgd door de Amerikaanse aanval in 1991, voor de Iraki’s de tweede Golfoorlog (de eerste Golfoorlog was de oorlog tussen Irak en Iran, van 1980 tot 1988).

Toen de Amerikaanse bommen het Iraakse leger uit Koeweit verdreven en de veelal dienstplichtige soldaten, die tegen hun zin Saddams oorlog uitvochten, halsoverkop in Basra arriveerden, brak daar de grote opstand tegen het Iraakse regime uit, niet in de laatste plaats vanwege de beruchte oproep van President George Bush sr. : “But there is another way to end the killing, to stop the bloodshed. And that is the Iraqi people have to take matters in their own hand and to force Saddam Husayn, the dictator, to step aside”. De terugkerende Iraakse troepen en de bevolking van de zuidelijke steden gaven, net als de Koerden in het noorden, gehoor aan die oproep, in der veronderstelling dat ze door de Amerikaanse tropenen op z’n minst beschermd zouden worden. Ook Mowaffk was, met andere studenten van de universiteit van Basra, zeer actief in de opstand tegen het Iraakse regime.

Binnen de kortste keren sloeg het regime terug. De opstandelingen waren geen partij voor de helikopters en tanks van de Republikeinse Garde. Vele opstandelingen, waaronder Mowaffk en zijn broer Ali, vluchtten de stad uit, de woestijn in en stuitten daar op de Amerikaanse troepen. De Amerikaanse soldaten hadden de strikte orders om de verzoeken om hulp niet in te willigen. Wel beloofden zij om grote aantallen opstandelingen in Saudi Arabië in veiligheid te brengen.

Aangekomen in Saudi Arabië droegen de Amerikanen de gevluchte Iraakse opstandelingen over aan het Saudische leger, dat hen opsloot in de beruchte kampen Rafha en Artawiyya. In het laatste kamp kwamen Mowaffk en zijn broer terecht, met zo’n 20.000 andere Iraakse vluchtelingen. Tot 1993 zaten zij daar, vergeten door de wereld, onder een onmenselijk regime van de Saudische kampbewakers, die hen als slaven behandelden en soms zelfs gevangenen voor flessen whisky verkocht aan de Iraakse geheime dienst. In 1993 wist een van de gevangenen te ontsnappen en Ryadh te bereiken. Vanuit het kantoor van BBC World lichtte hij de VN in en vanaf dat moment werd de wereld zich van hun bestaan bewust en werden de voormalige gevangenen door de VN verdeeld over verschillende landen. Mowaffk en zijn broer Ali werden aan Nederland toegewezen en zo kwam Mowaffk in Groningen terecht.

Sinds zijn vestiging in Nederland, eerst in Groningen, later Amsterdam, heeft Mowaffk al-Sawad aan een veelzijdig oeuvre gewerkt, als schrijver, dichter en beeldend kunstenaar. Het meest bekend is Stemmen onder de zon (de Passage, 2002), zijn ‘brievenroman’, over zijn tijd in Saudi Arabië. Daarnaast publiceerde hij enkele dichtbundels (zoals Een middag wit als melk, uitgeverij Bornmeer, 2002) en werden er gedichten van hem gepubliceerd in verschillende verzamelwerken (zoals Dwaallicht, tien Iraakse dichters in Nederland, de Passage, 2006).

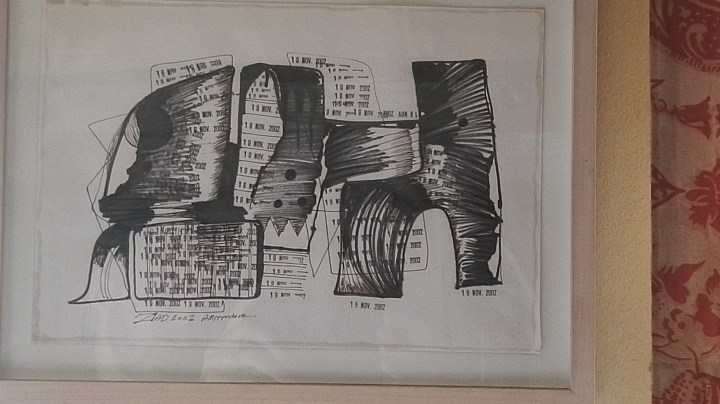

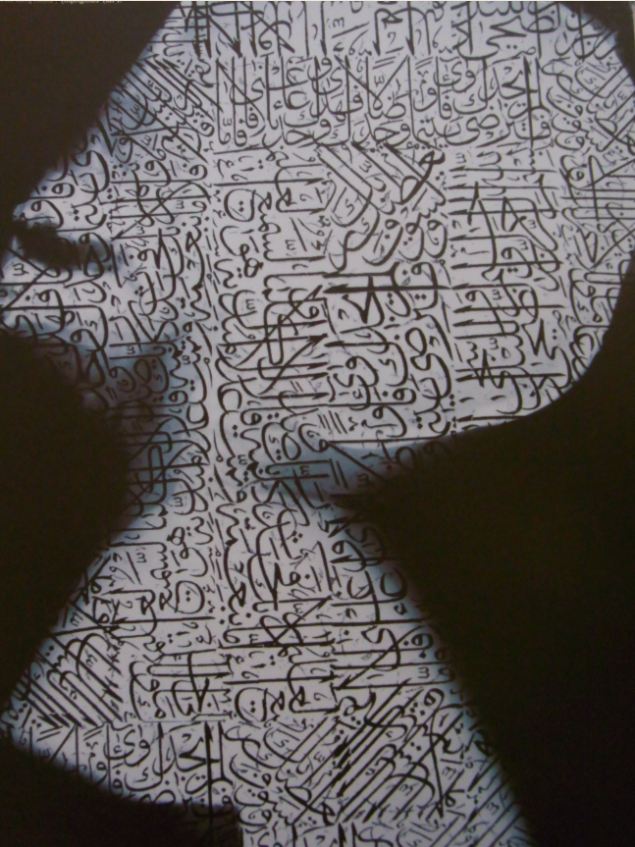

Mowaffk dicht zowel in het Nederlands als in het Arabisch. Dat dichten in twee talen betekent dat hij altijd een vertaalslag moet maken om een bepaald idee, een gevoel of wat dan ook uit te drukken. En onvermijdelijk dat in dat proces van vertalen ook iets van het origineel verloren gaat. Juist het dichten in ‘vertalingen’ heeft hem hier als geen ander van bewust gemaakt. Dit verlies in de vertaling- in Mowaffk al Sawads omschrijving “Het Gewiste” is dan ook het centrale thema in zijn beeldende kunst.

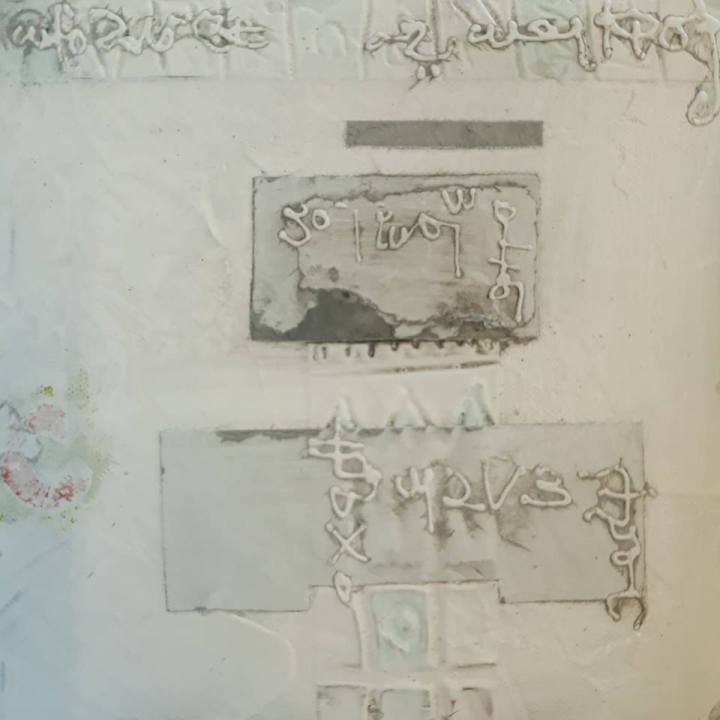

Voor de westerse kijker die niet bekend is met de Arabische taal of het alfabet, lijkt het alsof zijn schilderijen zijn bezaaid met Arabische teksten. Maar dat is schijn. Hoewel veel van de tekens doen denken aan Arabische letters, zijn het geen geschreven Arabische woorden, of geschreven woorden en zinnen in wat voor taal dan ook.

Mowaffk ziet zijn veelal in het wit opdoemende tekens als een voorstadium van de taal, of een voorstadium van het beeld. Misschien een vollediger of kernachtiger weergave/omschrijving dan mogelijk is het concrete geschreven woord of beeld. Want in de uiteindelijke materialisatie, de definitieve verschijningsvorm van taal en beeld, gaat er, zoals in elke vertaling, ook iets verloren. “Het gewiste”, aldus Mowaffk al-Sawad. Als een belangrijke inspiratiebron noemt hij de abstracte vormen van Juan Miro. Hij heeft hier eerder ook een gedicht aan gewijd. Uit zijn bundel ‘Een middag wit als melk’ (uitgeverij Bornmeer, Leeuwarden, 2002, p. 29):

De Kinderen van Juan Miro in hun Witte Tuin

Laat hem weggaan. Mijn fragiele lijf

ver, ver weg.

Laat hem gaan spelen met de kinderen van Juan Miro in hun witte tuin,

Waar handen zijn die niet kunnen zien,

voeten die vervagen,

het kleed dat weg is,

de dwalende schorpioenen,

en de slapende vlinder.

Waarheen, zuiderling, die vreemd is

In de steden van het noorden?

Welke ramp laat je nu smelten op je lippen,

Welke ruimte zal

Deze pijnlijke plaats van jou omvatten?

Glijd maar,

Alle kanten zijn omsingeld

En de blauwe punt is wazig.

Glijd maar,

De tuin is nog steeds wit en de vlinder vliegt bijna weg

Ogenschijnlijk staan de werken van Mowaffk al-Sawad in de traditie van de moderne kunst van de Arabische wereld waarin de Arabische letter of het teken centraal staat. Zoals bij de grote en zeer invloedrijke Iraakse kunstenaar Shakir Hassan al-Said (1925-2004). Of de Libische kunstenaar Ali Omar Ermes (1945). Of de Algerijnse kunstenaar Rachid Koraichi (1947)- met de laatste heeft het werk van Mowaffk al-Sawad nog de meeste formele overeenkomst. Maar er is een belangrijk verschil met deze ‘Arabische modernisten’ (door Brahim Alaoui, curator bij het Institut du Monde Arabe in Parijs, “l’Ecole de Signe” genoemd, de school van het teken). De werken van Mowaffk al-Sawad hebben een geheel ander conceptueel uitgangspunt, dan de grote Arabische modernisten die een verbinding zochten tussen de eigen kalligrafische traditie en de twintigste-eeuwse abstracte kunst.

De poging van Mowaffk al Sawad om het ‘gewiste’ te vangen zou je bijna Platoons kunnen noemen. Denk maar aan de metafoor van de Grot. Overigens is de Platoonse filosofie voor zowel de islamitische als de westerse traditie van groot belang geweest. En het is in beide tradities waarin Mowaffk al-Sawad, als kunstenaar en als dichter, opereert.

Floris Schreve

Amsterdam, 13 januari 2019

De tentoonstelling:

Exhibition I.M. Ziad Haider- زياد حيدر

IM Ziad Haider

Gallery Out in the Field

Warmondstraat 197, Amsterdam

27/5- 27/6/2018

http://www.art-gallery-outinthefied.com

زياد حيدر

Here the Original Dutch version

The abstract works of Ziad Haider (1954, Al-Amara, Iraq-2006 Amsterdam, the Netherlands) can be interpreted as deep reflections on his own turbulent biography, but always indirect, on a highly sublimized level. Born in Iraq and lived through a period of war and imprisonment, and after he found his destiny in the Netherlands, he left an impressive oeuvre.

Ziad Haider studied in the first half of the seventies at the Baghdad Institute of Fine Arts. In the two decades before a flourishing local and original Iraqi art scene was created. From the fifties till the seventies Iraq was one of the leading countries in the Arab world in the field of modern art and culture. Artists like Jewad Selim, Shakir Hassan al-Said and Mahmud Sabri shaped their own version of international modernism. Although these artists were educated abroad (mainly in Europe), after returned to Iraq they founded an art movement which was both rooted in the local traditions of Iraq as fully connected with the international developments in modernist art. They created a strong and steady basis for an Iraqi modern art, unless how much the Iraqi modern art movement would suffer from during the following decades of oppression, war and occupation, so much that it mainly would find its destiny in exile.

The turning-point came during the time Ziad Haider was studying at the academy. Artists who were a member of the ruling Ba’th party- or willing to become one- were promised an even international career with many possibilities to exhibit, as long as they were willing to express their loyalty to the regime, or even sometimes participate in propaganda-projects, like monuments, or portraits and statues of Saddam Husayn. Ziad Haider, who never joined the Ba’th party, was sent into the army.

In 1980 the Iraqi regime launched the long and destructive war with Iran. Many young Iraqis were sent into the army to fight at the frontline. This also happened to Ziad Haider. The Iraq/Iran war was a destructive trench war in which finally one million Iraqis (and also one million Iranians) died. The years of war meant a long interruption in Ziad Haider’s career and live as an artist. It turned out much more dramatic for him, when he was back in Baghdad for a short period at home. He was arrested after he peed on a portrait of Saddam Husayn. Ziad Haider was sent to Abu Ghraib Prison, where he stayed for five years (1986-1990) probably the darkest period of his life. After his time in prison he was sent away to the front again, this time in a new war: the occupation of Kuwait and the following American attack on Iraq.

After the Intifada of 1991, the massive uprising against the Iraqi regime in the aftermath of the Gulf War, which was violently supressed, Ziad Haider fled Iraq, like many others. After a period of five years in Syria and Jordan he was recognized by the UN as a refugee and was invited to live in the Netherlands, which became his new homeland. With a few paintings and drawings, he arrived 1997 in Amersfoort. After Amersfoort he lived for short a while in Almere and finally in Amsterdam. In first instance it was not simple to start all over again as an artist in his new country. Beside he worked further in his personal style he started to draw portraits in the streets of Amsterdam (the Leidse Plein and the Rembrandtplein). Later he organised, together with the Dutch artist Paula Vermeulen he met during this time and became his partner, several courses in drawing and painting in their common studio. Ziad Haider was very productive in this period and created many different works in different styles. Giving courses in figurative drawing and painting and drawing portraits was for him very important. As he told in a Dutch television documentary on five Iraqi artists in the Netherlands (2004, see here) these activities and the positive interaction with people were for him the best tools to “drive away his nightmares”.

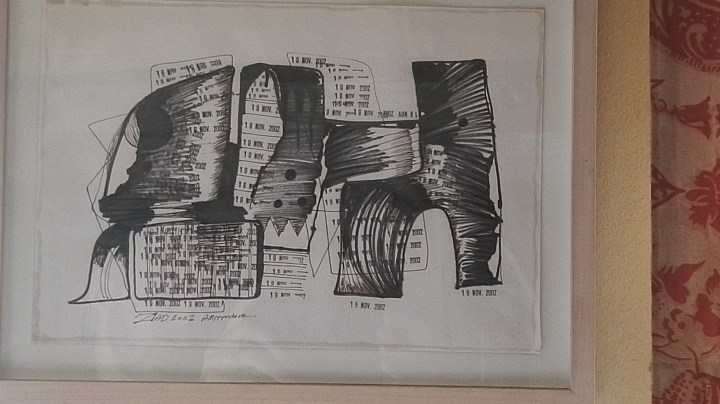

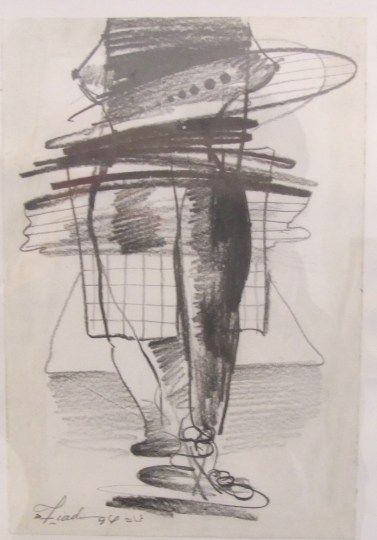

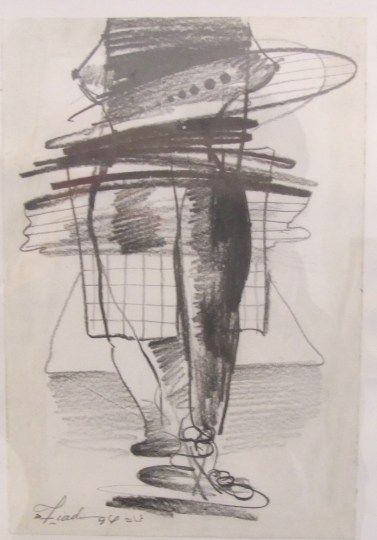

In his abstract works, always the main part of his artistic production, he sought the confrontation with the demons from the past. Although abstract there are often some recognisable elements, which are returning in several works during the years. A returning motive is the representation of his feet. This refers to several events from his own life. As a soldier Ziad had to march for days. When he was released from prison, together with some other prisoners, he was the only one who, although heavily tortured on his feet, who was able to stand up and walk. And his feet brought him further, on his long journey into exile, till he finally found a safe place to live and work.

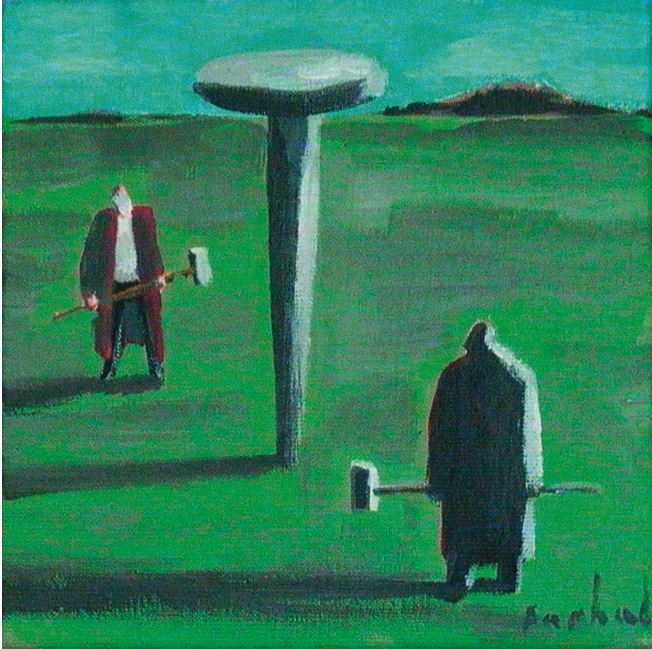

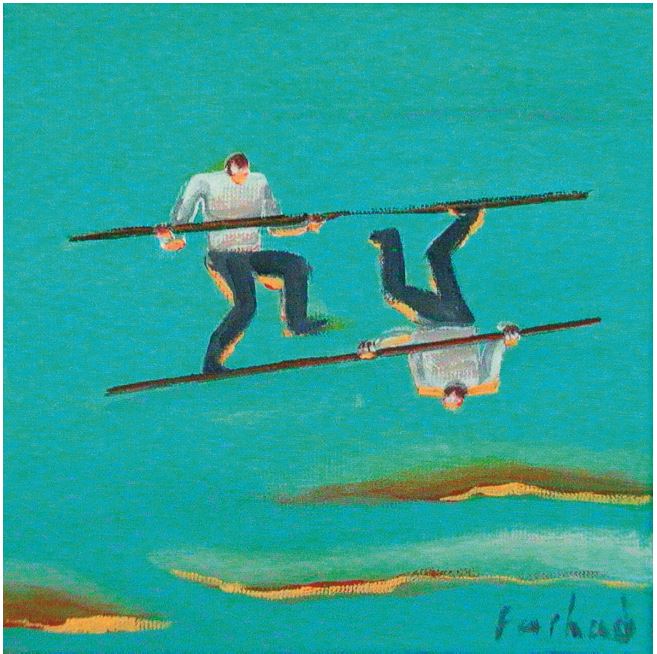

The motive of his bare feet is not the only figurative element in his work. In many of his paintings and drawings there are some more or less anthropomorphic elements, often molten together with structures with the appearance of liquid metal. The theme of man and machine plays an important role in the expressive works of Ziad. Of course this is close connected to his own biography and history of war and imprisonment.

In some of his works one can vividly experience a sense of a claustrophobic space, referring to his time spending in the trenches during the war, the interior of the tank and- later- the prison-cell. But all these experiences went through a process of transformation, of abstraction and translated in the language of art. And this art is, unless the underlying struggle, very lyrical in its expression.

The also in the Netherlands living Iraqi journalist, poet and critic Karim al-Najar wrote about Ziad Haider: “For a very long time the artist, Ziad Haider, has been living in solitude, prison and rebellion. On this basis, the foregoing works constitute his open protest against the decline, triviality and prominence of half-witted personalities as well as their accession of the authority of art and culture in Iraq for more than two decades. Here we could touch the fruits of the artist’s liberty and its reflection on his works. For Ziad Haider has been able to achieve works showing his artistic talent and high professionalism within a relatively short time. We see him at the present time liberated from his dark, heavy nightmares rapidly into their embodiment through colour and musical symmetry with the different situations. It indeed counts as a visual and aesthetic view of the drama of life as well as man’s permanent question, away from directness, conventionality and false slogans”.

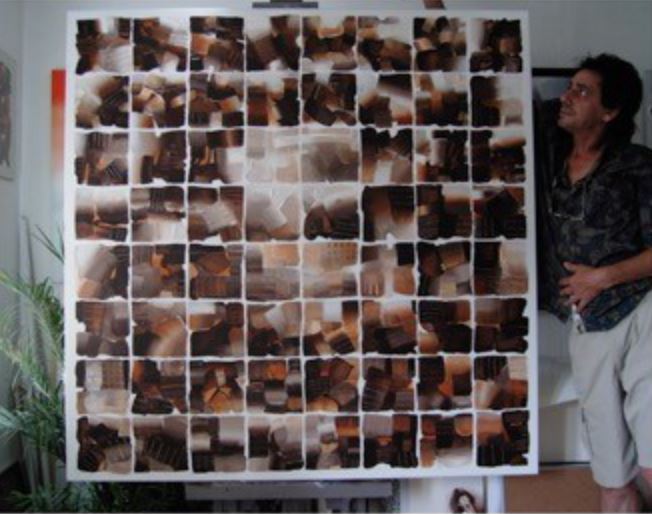

Although he opposed another American war against Iraq, with an uncertain outcome for its people, the end of the Ba’athist regime made it possible to visit his home country after many years of exile. In the autumn of 2003 he visited Iraq for the first time since his long absence in exile. His visit to iraq made a great impression and also influenced his work after. In the last series of paintings he made his use of colours changed dramatically. The explosive use of intense shades of red were replaced for a use of sober browns and greys. The dynamic compositions were changed in regular constructed forms. Also these works, from his last series, are represented on this exhibition.

Ziad meant a lot for many, as an artist, but also as a human being and a friend. Within the community of exiled Iraqi artists in the Netherlands he played a very important role. In 2004 he initiated the Iraqi cultural manifestation in Amsterdam, with the title “I cross the Arch of Darkness”, a quote from a poem by his friend, the also in the Netherlands living Iraqi poet Salah Hassan ( ﺃﻋﺒﺭﻗﻮﺲ ﻟﻟﻆﻻﻢ ﺃﻮﻤﻰﻋ ﻟﻟﻧﻬﺎﺭ ﺑﻌﻛﺎﺰﻱ , from his collected poems, published under the title “A rebel with a broken compass”, 1997). In this festival visual artists, poets, musicians and actors came together to show the variety and richness of the Iraqi cultual life in exile to a Dutch audience.

During the years Ziad and Paula lived at the Rozengracht in the old centre of Amsterdam, there home was a regular meetingpoint of many exiled Iraqi artists, poets, writers, musicians, actors, journalists and intellectuals. Many will cherish their sweet memories of the sometimes notorious gatherings till deep in the night. His sudden death in 2006 was a great loss for many of us.

The works of Ziad are still here and they deserve to be exhibited (now his second exhibition after he passed away). With this exhibition we celebrate Ziad Haider what he meant as an artist and as a human being.

Floris Schreve

Amsterdam, 2018

On this blog (mainly in Dutch):

Tentoonstelling Ziad Haider (Diversity and Art)

Iraakse kunstenaars in ballingschap

Modern and contemporary art of the Middle East and North Africa (English)

See also this In Memoriam of Ziad’s friend, the artcritic Amer Fatuhi

The opening:

Tentoonstelling IM Ziad Haider- زياد حيدر

IM Ziad Haider

Gallery Out in the Field

Warmondstraat 197, Amsterdam

27/5- 27/6/2018

http://www.art-gallery-outinthefied.com

زياد حيدر

Here the English version

Het abstracte werk van Ziad Haider (al-Amara, Irak, 1954-Amsterdam 2006) kan worden gezien als een diep doorleefde reflectie op zijn roerige levensgeschiedenis, zij het altijd in gesublimeerde vorm. Afkomstig uit Irak en, na een periode van oorlog en gevangenschap, uitgeweken naar Nederland, heeft hij, in de jaren dat hij werkzaam in Nederlandse ballingschap was, een groot aantal indrukwekkende werken nagelaten.

Ziad Haider studeerde begin jaren zeventig aan de kunstacademie in Bagdad.

In de twee decennia daarvoor was er in Irak een bloeiende modernistische kunstscene ontstaan. Vanaf de jaren vijftig tot in de jaren zeventig was Irak een van de meest toonaangevende landen op het gebied van moderne kunst en cultuur in de Arabische wereld. Iraakse kunstenaars als Jewad Selim, Shakir Hassan al-Said en Mahmud Sabri creëerden hun eigen versie van het internationale modernisme. Hoewel deze kunstenaars elders (vooral in Europa) waren opgeleid, trachtten zij, teruggekeerd naar hun geboorteland, een moderne kunstscene op te zetten, die zowel geworteld was in de lokale traditie, als aansloot bij de internationale ontwikkelingen. Zij creëerden hiermee een stevige basis voor een heel eigen Iraakse moderne kunsttraditie, hoezeer deze ook onder druk kwam te staan in de daaropvolgende decennia, vol met onderdrukking, oorlog en bezetting, waardoor vele Iraakse kunstenaars noodgedwongen hun werk in ballingschap moesten voortzetten.

In de tijd dat Ziad Haider studeerde kwam net het kantelpunt. Kunstenaars die lid van de regerende Ba’thpartij waren, konden, wanneer zij ook bereid waren om bij gelegenheid mee te werken met de verheerlijking van het regime en de officiële propaganda, soms een glanzende carrière tegemoetzien, tot en met de mogelijkheid tot exposeren in het buitenland. Ziad Haider, die geen lid van de Ba’thpartij was, werd na zijn studietijd meteen het leger ingestuurd.

Kort daarna, begin 1980, stortte het Iraakse regime zich in de oorlog met Iran. Vele jonge Iraki’s werden de oorlog ingestuurd om aan het front als soldaat te dienen en ook Ziad Haider trof dit lot. De Irak/Iran oorlog was een vernietigende loopgravenoorlog, waarin uiteindelijk een miljoen Iraki’s (en een miljoen Iraniërs) de dood vonden. De jaren van oorlog betekenden een lange onderbreking van Ziads loopbaan als kunstenaar. Zijn leven zou nog een veel heviger wending nemen toen hij midden jaren tachtig, gedurende een kort verlof in Bagdad, werd gearresteerd, omdat iemand over hem had geklikt bij de geheime dienst. Hij had over een portret van Saddam geplast. Voor bijna vijf jaar verbleef Ziad Haider in de beruchte Abu Ghraib gevangenis, de donkerste periode van zijn leven (1986-1990). Nadat hij was vrijgelaten werd hij weer terug het leger ingestuurd dat net Koeweit was binnengevallen. Ook de Golfoorlog van 1991 maakte hij volledig mee.

Na de volksopstand tegen het regime van 1991 ontvluchtte hij Irak. Voor vijf jaar verbleef hij achtereenvolgens in Syrië en Jordanië, totdat hij in 1997 als vluchteling aan Nederland werd toegewezen. Met een paar schilderijen en een serie tekeningen, kwam hij aan in ons land, waar hij terecht kwam in Amersfoort. Na Amersfoort woonde hij voor korte tijd in Almere en vervolgens in Amsterdam. Net als voor veel van zijn lotgenoten, was het in eerste instantie niet makkelijk om zich hier als kunstenaar te vestigen. Naast dat hij doorwerkte aan zijn persoonlijke stijl, werkte hij ook veel als portrettist en tekende hij portretten van passanten op het Leidse Plein en het Rembrandtplein. Later gaf hij, samen met Paula Vermeulen, die hij in die tijd ontmoette, ook verschillende teken- en schildercursussen in hun gemeenschappelijke atelier. Ziad Haider was in deze periode zeer productief, werkte met verschillende technieken in verschillende stijlen. Juist het werken met zijn cursisten of het tekenen van portretten op straat waren voor hem een belangrijke bron levenslust, zoals hij dat een keer verklaarde voor de IKON televisie, in een documentaire uit 2003: “Een manier om de terugkerende nachtmerries te verdrijven” (Factor, Ikon, 17-6-2003, zie hier).

In zijn abstracte werk ging Ziad Haider juist de confrontatie aan met de heftige gebeurtenissen uit zijn leven van de jaren daarvoor. In deze werken duiken ook een paar herkenbare elementen op, die regelmatig terugkeren in verschillende werken. Een motief dat op verschillende manieren terugkeert, is de weergave van zijn voeten. Dit gegeven refereert aan verschillende gebeurtenissen in zijn leven. Als soldaat moest Ziad Haider vaak lange marsen afleggen. Toen hij uit de gevangenis werd vrijgelaten was hij de enige van zijn medegevangenen die nog amper in staat was om op zijn voeten te staan. En natuurlijk hebben zijn voeten hem verder gedragen, op zijn lange reis in ballingschap, totdat hij uiteindelijk een veilige plaats vond.

Het motief van de voeten is niet het enige herkenbare gegeven in Ziads werken. Vaak zijn er min of meer antropomorfe elementen te ontdekken. Deze lijken vaak versmolten met vormen die doen denken aan gloeiend metaal. Het thema mens en machine speelt in het werk van Ziad een belangrijke rol. Ook dit thema hangt vanzelfsprekend nauw samen met zijn eigen geschiedenis van oorlog en gevangenschap.

Voelbaar is in sommige werken ook de claustrofobische ruimte, die refereert aan zijn verblijf in de loopgraven, de tank en daarna de cel, al zijn deze ervaringen altijd door een transformatieproces gegaan, waardoor ze zijn te vervatten in kunst. En deze kunst heeft, ondanks de strijd, vaak een buitengewoon lyrisch karakter.

De in Nederland wonende Iraakse journalist, dichter en criticus Karim al-Najar over Ziad Haider: ‘For a very long time the artist, Ziad Haider, has been living in solitude, prison and rebellion. On this basis, the foregoing works constitute his open protest against the decline, triviality and prominence of half-witted personalities as well as their accession of the authority of art and culture in Iraq for more than two decades. Here we could touch the fruits of the artist’s liberty and its reflection on his works. For Ziad Haider has been able to achieve works showing his artistic talent and high professionalism within a relatively short time. We see him at the present time liberated from his dark, heavy nightmares rapidly into their embodiment through colour and musical symmetry with the different situations. It indeed counts as a visual and aesthetic view of the drama of life as well as man’s permanent question, away from directness, conventionality and false slogans’.

Hoe zeer hij ook zijn bedenkingen had bij de Amerikaanse invasie van Irak in 2003, het betekende voor Ziad wel een mogelijkheid om weer zijn geboorteland te bezoeken. In de herfst van 2003 zette hij deze stap. Zijn bezoek aan Irak maakte grote indruk en had ook zijn weerslag op de laatste serie werken die hij maakte. Allereerst veranderde zijn palet. Het intense rood, dat zijn werken voor die tijd sterk had gedomineerd, werd vervangen door sobere bruinen en grijzen. De heftige bewegingen in zijn composities maakten plaats voor een regelmatiger opbouw. Ook dat werk, uit zijn laatste reeks, is op deze tentoonstelling te zien.

Ziad heeft veel betekend als kunstenaar, maar verder was hij ook een belangrijk figuur binnen de Iraakse kunstscene in ballingschap. Zo was hij de initiatiefnemer van het de manifestatie “Ik stap over de Boog van Duisternis; Iraakse kunstenaars in Amsterdam”. Onder deze titel , die verwijst naar een zin uit een gedicht van de dichter en Ziads vriend Salah Hassan, ( “ﺃﻋﺒﺭﻗﻮﺲ ﻟﻟﻆﻻﻢ ﺃﻮﻤﻰﻋ ﻟﻟﻧﻬﺎﺭ ﺑﻌﻛﺎﺰﻱ ” , uit de bundel Een rebel met een kapot kompas, 1997), werd er in 2004 een Iraaks cultureel festival in Amsterdam georganiseerd, waarin verschillende uit Irak afkomstige beeldende kunstenaars, dichters, musici en acteurs centraal stonden.

Gedurende de jaren dat Ziad en Paula samen aan de Rozengracht woonden, was hun huis een trefpunt van vele Iraakse beeldende kunstenaars, maar ook dichters, schrijvers, musici, acteurs en journalisten. Velen zullen dierbare herinneringen koesteren aan deze roemruchte avonden. Het plotselinge overlijden van Ziad Haider in 2006 kwam dan ook als een grote klap.

Zijn werk is er gelukkig nog en verdient het om getoond te worden. Met deze tentoonstelling vieren wij wat hij als kunstenaar en als mens heeft betekend.

Floris Schreve

Amsterdam, mei 2018

Verder op dit blog:

Tentoonstelling Ziad Haider (Diversity and Art)

Iraakse kunstenaars in ballingschap

Zie ook deze In Memoriam van de Iraakse kunstcriticus Amer Fatuhi

De opening:

Lecture: A history of Iraqi modern art and Iraqi artists in the Diaspora, on the occasion of the exhibition ‘Distant Dreams; the other face of Iraq’, Kunstliefde (Utrecht)

http://onglobalandlocalart.wordpress.com/2012/02/28/

Handout of my lecture on Iraqi modern art and Iraqi artists in the Diaspora, Kunstliefde, Utrecht, The Netherlands, 24 February 2012, on the occasion of the exhibition Distant Dreams; five Iraqi artists in the Netherlands (Baldin Ahmad, Qassim Alsaedy, Salam Djaaz, Awni Sami and Araz Talib), with the addition of some of the visual material (click on the pictures to enlarge)

Introduction on the history and geography of Iraq

Origins and development of the Iraqi modern art (from 1950)

Jewad Selim Faeq Hassan Shakir Hassan al-Said

Mahmud Sabri Dhia Azzawi Rafa al-Nasiri

Mohammed Mohreddin Hanaa Mal-Allah

Art and mass-propaganda under the rule of the Ba’th Party

Al-Nasb al-Shaheed (‘The Martyr’s Monument’, by Ismael Fattah al-Turk)

Bab al-Nasr ( ‘Victory Arch’, designed by Saddam Husayn and executed by Khalid al-Rahal and Mohammed Ghani Hikmet)

Statues and portraits of Saddam Husayn and Michel Aflaq (founder of the Ba’thparty)

Iraqi artists in the Diaspora

The Netherlands:

Baldin Ahmad Aras Kareem Hoshyar Rasheed

Araz Talib Awni Sami Salam Djaaz

Qassim Alsaedy Ziad Haider Nedim Kufi

Rebwar Saeed (England) Anahit Sarkes (England)

Jananne al-Ani (England) Ahmed al-Sudani (United States)

Walid Siti (England) Halim Al Kareem (Netherlands/United States)

Adel Abidin (Finland) Azad Nanakeli (Italy)

Ali Assaf (Italy) Wafaa Bilal (United States)

On the screen a work of Mahmud Sabri, one of the most experimental Iraqi artists in history

A work of Jewad Selim, more or less the ‘founder of the Iraqi modern art’

On the screen a work of Shakir Hassan al-Said, whose style influenced artists all over the Arab and even the islamic world

Left (in front) Qassim Alsaedy. Me behind the laptop. Behind me (left side) my sister Leonie Schreve and her partner Anand Kanhai. Behind them the Iraqi artist Ali Talib. Second right of me Brigitte Reuter, who created many works together with Qassim Alsaedy. On the walls (right) the work of Awni Sami

Left behind me Martin van der Randen, curator of this exhibition. Left on the wall the work of Baldin Ahmad

Tentoonstelling ‘Distant Dreams; the other face of Iraq’ (Kunstliefde, Utrecht)

أحلام بعيدة، هي الوجه الآخر للعراق

معرض لخمسة فنانين عراقيين في هولندا

On Sunday February 19th in Utrecht (in the artists Society Kunstliefde) the exhibition ‘Distant Dreams, the other face of Iraq’ will be opened, an exhibition of five Iraqi artists who are living and working in the Netherlands, curated by Martin van der Randen. The participating artists are Salam Djaaz, Qassim Alsaedy, Baldin Ahmad, Awni Sami and Araz Talib , all on this blog ever mentioned or extensively discussed. On Friday, February 24 at 20:00 I will give a lecture at the exhibition on the history of modern art of Iraq and the Iraqi art in the Diaspora, in the Netherlands and elsewhere.

Here is the brochure of Distant Dreams; The other face of Iraq (both in English and Dutch)

In this blog entry, the documentation of the exhibition and the lecture will appear very soon. Below the official announcement. See also http://www.iraqiart.com/inp/view.asp?ID=1305 (Arabic):

Op zondag 19 februari wordt in de Utrechtse kunstenaarsvereniging Kunstliefde de tentoonstelling Distant Dreams; the other face of Iraq geopend, van vijf uit Irak afkomstige kunstenaars in Nederland, samengesteld door Martin van der Randen. De deelnemende kunstenaars zijn Salam Djaaz, Qassim Alsaedy, Baldin Ahmad, Awni Sami en Araz Talib, allen weleens op dit blog genoemd of uitvoerig besproken. Op vrijdag 24 februari zal ik om 20.00 bij de tentoonstelling een lezing geven over de geschiedenis van de moderne kunst van Irak en de Iraakse kunst in de Diaspora, in Nederland en elders.

Zie hier de Brochure van Distant Dreams; The other face of Iraq

In dit blogitem zal de documentatie van de tentoonstelling en de lezing verschijnen. Hieronder de officiële aankondiging.

Lezing op 24 februari, om 20.00 in Kunstliefde, Nobelstraat 12A, Utrecht (www.kunstliefde.nl)

(أمستردام، هولندا)

Opening (Sunday February 19th, 2012)

Qassim Alsaedy (l), Salam Djaaz (r)

Awni Sami (l), Baldin Ahmad (r)

Araz Talib

The writers/journalists Ishin Mohiddin (l), Karim Al-Najar (r)

Mrs Mayada al-Gharqoly of the Iraqi Embassy in the Netherlands. Behind her Martin van der Randen, curator of this exhibition

Mayada al-Gharqoly

Mounir Goran (ud), with the Dutch Kurdish Iraqi poet Baban Kirkuki

The Dutch Iraqi Kurdish writer Ibrahim Selman (l) with Qassim Alsaedy

From the left to the right: Baban Kirkuki, Mounir Goran, Qassim Alsaedy, Baldin Ahmad, Araz Talib, Salam Djaaz, Awni Sami

Finissage (Sunday March 18th, 2012)

Qassim Alsaedy with HE Dr. Saad Ibrahim al-Ali, Embassador of Iraq in the Netherlands

The embassador, with some other staff of the Embassy and some of the artists

Martin van der Randen with Baldin Ahmad

Baldin Ahmad and Salam Djaaz

Baldin Ahmad and Qassim Alsaedy

Baban Kirkuki, Salam Djaaz and Munir Goran

photos by Floris Schreve

Kunstenaars uit de Arabische wereld in Nederland (verschenen in Eutopia nr. 27, april 2011 ‘Diversiteit in de Beeldende Kunst’) – فنانون من العالم العربي في هولندا

Mijn artikel, dat afgelopen voorjaar in Eutopia is verschenen (Eutopia nr. 27, april 2011, themanummer ‘Diversiteit in de Beeldende Kunst’, zie hier). Het artikel heb ik echter geschreven in het najaar van 2010, dus nog vóór de opstanden in de Arabische wereld. Hoewel het onderwerp natuurlijk kunstenaars uit de Arabische wereld in Nederland was, zou ik er zeker een opmerking over hebben gemaakt. De Arabische Lente, die in Tunesië begon nadat op 17 december 2010 in Sidi Bouzid de 27 jarige Mohamed Bouazizi zichzelf in brand stak en daarmee de onvrede van de relatief jonge Arabische bevolking met de zittende dictatoriale regimes van de diverse landen een gezicht gaf, is, los van hoe de ontwikkelingen verder zullen gaan, natuurlijk een historische mijlpaal zonder weerga. Maar het begin van de Arabische opstanden voltrok zich precies tussen het moment dat ik onderstaande bijdrage had ingestuurd (november 2010) en de uiteindelijke verschijning in mei 2011. In een later geschreven bijdrage voor Kunstbeeld, over moderne en hedendaagse kunst in de Arabische wereld zelf, heb ik wel aandacht aan deze ontwikkelingen besteed, zie hier.

Het nummer van Eutopia was vrijwel geheel gewijd aan kunstenaars uit Iran in Nederland. In de verschillende bijdragen van Özkan Gölpinar, Neil van der Linden, Robert Kluijver, Dineke Huizenga, Bart Top, Marja Vuijsje, Wanda Zoet en anderen kwamen vooral Iraanse kunstenaars aan bod, als Soheila Najand, Atousa Bandeh Ghiasabadi, Farhad Foroutanian, (de affaire) Sooreh Hera en nog een aantal anderen. In mijn bijdrage heb ik me gericht op de kunstenaars uit de Arabische landen, die wonen en werken in Nederland, die ook een belangrijke rol speelden in mijn scriptie-onderzoek.

De tekst is vrijwel dezelfde als die van de gedrukte versie, alleen heb ik een flink aantal weblinks toegevoegd, die verwijzen naar websites van individuele kunstenaars, achtergrondartikelen en documentaires, of radio- en televisie-uitzendingen.

Hieronder mijn bijdrage aan dit themanummer:

Kunstenaars uit de Arabische wereld in Nederland

فنانون من العالم العربي في هولندا

Naast dat er een aantal uit Iran afkomstige kunstenaars in ons land actief zijn, zijn er ook veel kunstenaars uit de Arabische landen, die wonen en werken in Nederland. Je zou deze groep migrantkunstenaars in drie categorieën kunnen verdelen.

Allereerst zijn er zo’n twintig kunstenaars die vanaf de jaren zeventig naar Europa en uiteindelijk naar Nederland kwamen om hun opleiding te voltooien en hier gebleven zijn. Te denken valt aan Nour-Eddine Jarram en Bouchaib Dihaj (Marokko), Abousleiman (Libanon), Baldin (Iraaks Koerdistan), Saad Ali (Irak, inmiddels verhuisd naar Frankrijk), Essam Marouf , Shawky Ezzat, Achnaton Nassar (Egypte) en van een iets latere lichting Abdulhamid Lahzami en Chokri Ben Amor (Tunesië) . [1]

Achnaton Nassar, bijvoorbeeld, kwam naar Nederland om verder te studeren aan de Rijksacademie. Hij werd in 1952 in Qena, Egypte, geboren en studeerde aan de universiteiten van Alexandrië en Cairo. Hier werd hij opgeleid in de islamitische traditie, waarbij het Arabische alfabet als uitgangspunt diende. Nassar vond dit te beperkt. De drang om zich verder te ontwikkelen dreef hem naar Europa. Na een studie architectuur in het Griekse Saloniki deed Nassar zijn toelatingsexamen voor de Rijksacademie, te Amsterdam. Daarna vestigde hij zich in 1982 in Amstelveen.

Het grootste deel van Nassars werk bestaat uit abstracte tekeningen, waarbij hij verschillende technieken inzet. In zijn composities verwijst Nassar vaak naar de abstracte vormtaal van de islamitische kunst en het Arabische schrift, al verwerkt hij deze met de organische vormen die hij hier in bijvoorbeeld het Amsterdamse bos aantreft, dat vlakbij zijn atelier ligt. [2]

In de jaren negentig heeft Nassar een serie popart-achtige figuratieve werken gemaakt, die een dwarse kijk geven op het toen net oplaaiende debat over ‘de multiculturele samenleving’. In deze serie werken combineert Nassar clichébeelden van wat de Nederlandse identiteit zou zijn, met clichébeelden die hier bestaan van de Arabische cultuur. Door op een ironische manier beide stereoptype beelden te combineren, worden beiden gerelativeerd of ontzenuwd.

Een voorbeeld is het hier getoonde paneel uit de periode 1995-2000. Het werk verwijst naar het bankbiljet voor duizend gulden, waarop het portret van Spinoza staat weergegeven. Door kleine interventies is het beeld van betekenis veranderd. Het gebruikelijke 1000 gulden is vervangen met 1001 Nacht en ‘De Nederlandsche Bank’ is veranderd in ‘De Wereldliteratuurbank’. Het biljet is getekend door president N. Mahfouz op 22 juli 1952, de dag van de Egyptische revolutie en bovendien Nassars geboortedag. Een opmerkelijk detail zijn de met goudverf aangebrachte lijnen in het gezicht van Spinoza. Deze lijnen, die lopen vanaf het profiel van de neus via de rechter wenkbrauw naar het rechteroog, vormen het woord Baruch in het Arabisch, Spinoza’s voornaam. Op deze wijze plaatst Nassar een Nederlands symbool als het duizend gulden biljet in een nieuwe context. Spinoza was immers in zijn tijd ook een vreemdeling, namelijk een nazaat van Portugese Joden. Met een werk als dit stelt Nassar belangrijke vragen over nationale versus hybride identiteit en maakt hij een statement over de betrekkelijkheid van symboliek als een statisch referentiepunt van nationale identificatie. [3]

Ook de andere figuratieve werken van Nassar staan vol met dit soort verwijzingen. De essentie van zijn werk ligt in hoe de een naar de ander kijkt en de ander weer naar de één. De ‘oosterling’ kijkt naar de ‘westerling’ volgens een bepaald mechanisme, maar Nassar heeft vooral dit thema in omgekeerde richting verwerkt: wat is de cultureel bepaalde blik van het ‘Westen’ naar de ‘Oriënt’?

Achnaton Nassar, Zonder titel, acryl op paneel, 1995-1996 (afb. collectie van de kunstenaar)

Met zijn beeldinterventies legt Nassar valse neo-koloniale en exotistische structuren bloot, die in het westerse culturele denken bestaan. Hiermee raakt hij een belangrijk punt van de westerse cultuurgeschiedenis. Volgens de Palestijnse literatuurwetenschapper Edward Said bestaat er een groot complex aan cultureel bepaalde vooroordelen in de westerse culturele canon wat betreft de ‘Oriënt’. In zijn belangrijkste werk, Orientalism (1978), heeft hij erop gewezen dat de beeldvorming van het westen van de Arabische wereld vooral wordt bepaald door enerzijds een romantisch exotisme en anderzijds door een reactionaire kracht die, in de wil tot overheersing, de ‘irrationaliteit’ van de ‘Oriënt’ wil indammen, daar zij nooit zelf in staat zou zijn om tot vernieuwingen te komen. Said heeft in zijn belangrijke wetenschappelijke oeuvre (Orientalism en latere werken) de onderliggende denkstructuren blootgelegd, die hij toeschrijft aan het imperialistische gedachtegoed, een restant dat is gebleven na de koloniale periode en nog steeds zijn weerslag vindt in bijvoorbeeld de wetenschap (zie Bernard Lewis, maar van iets later bijvoorbeeld ook de notie van de ‘Clash of Civilizations’ van Samuel Huntington, die sterk op het gedachtegoed van Lewis is geïnspireerd- het begrip ‘Clash of Civilizations’ is zelfs ontleend aan een passage uit Lewis’ artikel The Roots of the Muslim Rage uit 1990), de media en de politiek. [4] Ook voor het debat in de hedendaagse kunst is Saids bijdrage van groot belang geweest. Op dit moment speelt het discours zich af tussen processen van uitsluiting, het toetreden van de ander (maar daarbij het insluipende gevaar van exotisme), of gewoon dat goede kunst van ieder werelddeel afkomstig kan zijn.

De overgrote meerderheid van de kunstenaars uit de Arabische wereld in Nederland bestaat vooral uit kunstenaars uit Irak, die grotendeels in de jaren negentig naar Nederland zijn gekomen als politiek vluchteling voor het vroegere Iraakse regime. Het gaat hier om zo’n tachtig beeldende kunstenaars, zowel van Arabische als Koerdische afkomst. Naast beeldende kunstenaars zijn er overigens ook veel dichters (bijv. Salah Hassan, Naji Rahim, Chaalan Charif en al-Galidi ), schrijvers (Mowaffk al-Sawad en Ibrahim Selman), musici (zoals het beroemde Iraqi Maqam ensemble van Farida Mohammed Ali, de fluitist / slagwerker Sattar Alsaadi, de zanger Saleh Bustan en het Koerdische gezelschap Belan, van oa Nariman Goran) en acteurs (bijv. Saleh Hassan Faris) in die tijd naar Nederland gekomen. [5]

Beeldende kunstenaars uit Irak die zich de afgelopen jaren in Nederland hebben gemanifesteerd zijn oa Ziad Haider (helaas overleden in 2006, zie ook dit artikel op dit blog), Aras Kareem (zie ook hier op dit blog), Monkith Saaid (helaas overleden in 2008), Ali Talib , Afifa Aleiby, Nedim Kufi (zie op dit blog hier en hier), Halim al Karim (verhuisd naar de VS, overigens nu op de Biënnale van Venetië, zie dit artikel), Salman al-Basri, Mohammed Qureish, Hoshyar Rasheed (zie ook op dit blog), Sadik Kwaish Alfraji, Sattar Kawoosh , Iman Ali , Hesam Kakay, Fathel Neema, Salam Djaaz, Araz Talib, Hareth Muthanna, Awni Sami, Fatima Barznge en vele anderen. [6]

Een Iraakse kunstenaar, die sinds de laatste jaren steeds meer boven de horizon van ook de Nederlandse gevestigde kunstinstellingen is gekomen, is Qassim Alsaedy (Bagdad 1949). Alsaedy studeerde in de jaren zeventig aan de kunstacademie in Bagdad, waar hij een leerling was van oa Shakir Hassan al-Said, een van de meest toonaangevende kunstenaars van Irak en wellicht een van de meest invloedrijke kunstenaars van de Arabische en zelfs islamitische wereld van de twintigste eeuw. [7] Gedurende zijn studententijd kwam Alsaedy al in conflict met het regime van de Ba’thpartij. Hij werd gearresteerd en zat negen maanden gevangen in al-Qasr an-Nihayyah, het beruchte ‘Paleis van het Einde’, de voorloper van de latere Abu Ghraib gevangenis.

Na die tijd was het voor Alasedy erg moeilijk om zich ergens langdurig als kunstenaar te vestigen. Hij woonde afwisselend in Syrië, Jemen en in de jaren tachtig in Iraaks Koerdistan, waar hij leefde met de Peshmerga’s (de Koerdische rebellen). Toen het regime in Bagdad de operatie ‘Anfal’ lanceerde, de beruchte genocide campagne op de Koerden, week Alsaedy uit naar Libië, waar hij zeven jaar lang als kunstenaar actief was. Uiteindelijk kwam hij midden jaren negentig naar Nederland.

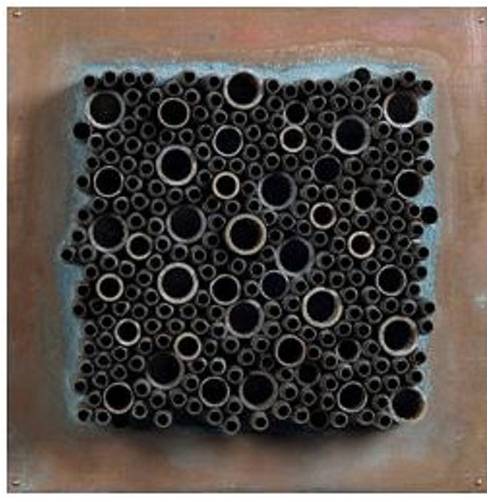

Qassim Alsaedy, object uit de serie/installatie Faces of Baghdad, assemblage van metaal en lege patroonhulzen op paneel, 2005 (geëxposeerd op de Biënnale van Florence van 2005). Afb. collectie van de kunstenaar

In het werk van Alsaedy staan de afdrukken die de mens in de loop van geschiedenis hebben achterlaten centraal. Hij is vooral gefascineerd door oude muren, waarop de sporen van de geschiedenis zichtbaar zijn. In zijn vaderland Irak, het gebied van het vroegere Mesopotamië, werden al sinds duizenden jaren bouwwerken opgetrokken, die in de loop van de geschiedenis weer vergingen. Telkens weer liet de mens zijn sporen na. In Alsaedy’s visie blijft er op een plaats altijd iets van de geschiedenis achter. In een bepaald opzicht vertoont het werk van Qassim Alsaedy enige overeenkomsten met het werk van de bekende Nederlandse kunstenaar Armando . Toch zijn er ook verschillen; waar Armando in zijn ‘schuldige landschappen’ tracht uit te drukken dat de geschiedenis een blijvend stempel op een bepaalde plaats drukt (zie zijn werken nav de Tweede Wereldoorlog en de concentratiekampen van de Nazi’s), laat Alsaedy de toeschouwer zien dat de tijd uiteindelijk de wonden van de geschiedenis heelt. [8]

Het hier getoonde werk gaat meer over de recente geschiedenis van zijn land. Alsaedy maakte deze assemblage van lege patroonhulzen na zijn bezoek aan Bagdad in de zomer van 2003, toen hij na meer dan vijfentwintig jaar voor het eerst weer zijn geboorteland bezocht. Vanzelfsprekend is dit werk een reactie op de oorlog die dat jaar begonnen was. Maar ook deze ‘oorlogsresten’ zullen uiteindelijk wegroesten en verdwijnen, waarna er slechts een paar gaten of littekens achterblijven.

Sinds de laatste tien jaar begint ook de tweede generatie migrantenkunstenaars uit de Arabische wereld zichtbaar te worden. De tot nu toe meest bekende kunstenaar uit deze categorie is de Nederlandse/ Marokkaanse kunstenaar Rachid Ben Ali. Ben Ali bezocht kortstondig de mode-academie en de kunstacademie in Arnhem, maar vestigde zich al snel als autonoom kunstenaar in Amsterdam. Sinds die tijd heeft hij een stormachtige carrière doorgemaakt. Hij werd ‘ontdekt’ door Rudi Fuchs, exposeerde in het Stedelijk op de tentoonstelling die was samengesteld door Koningin Beatrix en had een paar grote solo-exposities, waaronder in Het Domein in Sittard (2002) en in het Cobramuseum in Amstelveen (2005). Deze tentoonstellingen verliepen overigens niet zonder controverses. Vanuit de islamitische hoek, maar zeker ook vanuit de autochtone Nederlandse hoek (zoals in de gemeente van Sittard, toen Ben Ali in het Domein exposeerde in 2002), werd het werk van Ben Ali als provocerend of aanstootgevend ervaren, vooral vanwege de expliciet homo-erotische voorstellingen die hij had verbeeld. [9]

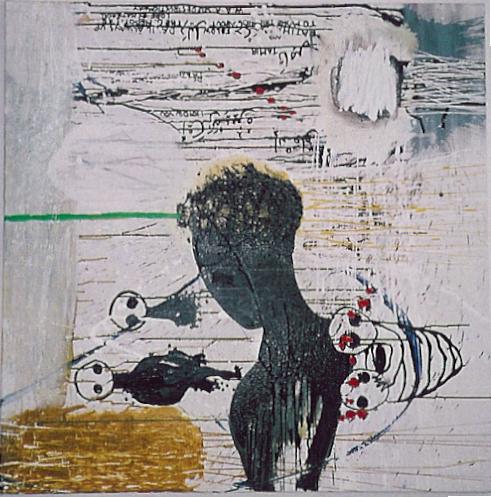

Het werk van Ben Ali is rauw, direct, intuïtief en soms confronterend. In zijn werk zijn persoonlijke en politieke thema’s met elkaar verweven. Een belangrijke rol spelen zijn persoonlijke achtergrond, zijn homoseksualiteit, zijn verontwaardiging over zowel racisme en vreemdelingenhaat, als over religieuze bekrompenheid en intolerantie en zijn betrokkenheid bij wat er in de wereld gebeurt. Het hier getoonde werk maakte Ben Ali naar aanleiding van beelden van doodgeschoten Palestijnse kinderen door het Israëlische leger. Het weergegeven silhouet is een verbeelding van zijn eigen schaduw. Ben Ali heeft zichzelf hier weergeven als een machteloze toeschouwer, die van een grote afstand niet in staat is om iets te doen, behalve te aanschouwen en te getuigen. [10]

Er zijn nog veel meer kunstenaars uit de Arabische wereld in Nederland actief, zowel uit het Midden Oosten als Noord Afrika. Het is vanzelfsprekend onmogelijk om hen allemaal in dit verband recht te doen. Hoewel de meesten nog onbekend zijn bij de gevestigde instellingen, neemt hun zichtbaarheid in de Nederlandse kunstwereld langzaam maar zeker toe.

Floris Schreve,

Amsterdam, november 2010

فلوريس سحرافا

امستردام، 2010

Zie in dit verband ook mijn recente uitgebreide tekst over Qassim Alsaedy, nav de tentoonstelling in Diversity & Art en de bijdragen rond mijn lezing (de handout, mijn bijdrage in Kunstbeeld en de Engelse versie, waarin ik beiden heb samengevoegd) over de hedendaagse kunst in de Arabische wereld, waarin de actuele gebeurtenissen wel uitgebreid aan de orde zijn gekomen

Rachid Ben Ali, Zonder Titel, acryl op doek, 2001 (foto Floris Schreve)

Noten

[1] Tineke Lonte, Kleine Beelden, Grote Dromen, Al Farabi, Beurs van Berlage, Amsterdam, 1993 (zie ook Jihad Abou Sleiman, Arabische kunstenaars schilderen bergen in Nederland, in Rosemarie Buikema, Maaike Meijer, ‘Cultuur en Migratie in Nederland; Kunst in Beweging 1980-2000’, Sdu Uitgevers, Den Haag, 2004, pp. 237-252, http://www.dbnl.org/tekst/meij017cult02_01/meij017cult02_01_0015.php) ; Mili Milosevic, Schakels, Museum voor Volkenkunde (Wereldmuseum), Rotterdam, 1988; Jetteke Bolten, Els van der Plas, Het Klimaat: Buitenlandse Beeldende Kunstenaars in Nederland, Gate Foundation, Stedelijk Museum de Lakenhal, Culturele Raad Zuid Holland, Den Haag, 1991; Paul Faber, Sebastian López, Double Dutch; transculturele beïnvloeding in de beeldende kunst, Stichting Kunst Mondiaal, Tilburg, 1992 (zie hier de introductie); Els van der Plas, Anil Ramdas, Sebastian López, Het land dat in mij woont: literatuur en beeldende kunst over migratie, Gate Foundation, Museum voor Volkenkunde (Wereldmuseum), Rotterdam, 1995.

[2] Hans Sizoo, ‘Nassar, het park en de Moskee’, in J. Rutten (red.) met bijdragen van Kitty Zijlmans, Floris Schreve, Hans Sizoo, Achnaton Nassar, Saskia en Hassan gaan trouwen, werken van Achnaton Nassar, Universiteitsbibliotheek Leiden, 2001. Zie ook http://www.dripbook.com/achnatonnassar/splash/ en voor meer abstract werk (tekeningen), zie de site van Galerie Art Singel 100, http://www.artxs.nl/achnaton.htm

[3] Saskia en Hassan (2001), zie ook de online versie http://bc.ub.leidenuniv.nl/bc/tentoonstelling/Saskia_en_hassan/

[4] Edward Said, Orientalism; Western conceptions of the Orient, Pantheon Books, New York, 1978 (repr. Penguin Books, New York 1995, 2003). Zie ook: Samuel Huntington, The Clash of Civilizations?, Foreign Affairs, vol. 72, no. 3, Summer 1993; Bernard Lewis, The Roots of the Muslim Rage, The Atlantic Monthly, September 1990, http://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/1990/09/the-roots-of-muslim-rage/4643/ , Edward Said, The Clash of Ignorance, The Nation, 4 October, 2001, http://www.thenation.com/article/clash-ignorance

[5] Zie bijv. Chaalan Charif, Dineke Huizenga, Mowaffk al-Sawad (red.), Dwaallicht; tien Iraakse dichters in Nederland (poëzie van Mohammad Amin, Chaalan Charif, Venus Faiq, Hameed Haddad, Balkis Hamid Hassan, Salah Hassan, Karim Nasser, Naji Rahim, Mowaffk al-Sawad en Ali Shaye), de Passage, Groningen, 2006; Mowaffk al-Sawad, Stemmen onder de zon, uitgeverij de Passage, Groningen (roman, gebundelde brieven), 2002; Ibrahim Selman, En de zee spleet in tweeën, in de Knipscheer, Amsterdam, 2002 (roman) en de website van Al Galidi http://www.algalidi.com/. Over Iraakse schrijvers in Nederland Dineke Huizenga, Parels van getuigenissen, Zemzem; Tijdschrift over het Midden Oosten, Noord Afrika en islam, themanummer ‘Nederland en Irak’, jaargang 2, nr. 2/ 2006, pp. 56-63 en over Iraakse musici in Nederland Neil van der Linden, Muzikant in Holland, idem, pp. 82-87

[6] Zie oa W. P. C. van der Ende, Versluierde Taal, vijf uit Irak afkomstige kunstenaars in Nederland, Museum Rijswijk, Vluchtelingenwerk Rijswijk, 1999; IMPRESSIES; Kunstenaars uit Irak in ballingschap, AIDA Nederland, Amsterdam, 1996; Ismael Zayer, 28 kunstenaars uit Irak in Nederland, de Babil Liga voor de letteren en de kunsten, Gemeentehuis Den Haag, 2000; Anneke van Ammelrooy, Karim al-Najar, Iraakse kunstenaars in het Museon, Babil, Den Haag, november, 2002; Floris Schreve, Out of Mesopotamia; Iraakse kunstenaars in ballingschap, Leidschrift, Vakgroep Geschiedenis Universiteit Leiden, 17-3-2002 (bewerkte versie Iraakse kunst in de Diaspora, verschenen in Eutopia, nr. 4, april 2003, pp. 45-63); Floris Schreve, Kunst gedijt ook in ballingschap, Zemzem; Tijdschrift over het Midden Oosten, Noord Afrika en islam, themanummer ‘Nederland en Irak’, jaargang 2, nr. 2/ 2006, pp. 73-80 (online versie: https://fhs1973.wordpress.com/2009/06/16/ ); Helge Daniels, Corien Hoek, Charlotte Huygens, Focus Irak, programma en catalogus van het Iraakse culturele festival/tentoonstelling in het Wereldmuseum, ism de Stchting Akkaad, Rotterdam, mei 2004 (zie http://www.akaad.nl/archief.php); programma ‘Iraakse kunsten in Amsterdam’ (2004), zie http://aidanederland.nl/wordpress/archief/discipline/multidisciplinair/seizoen-2004-2005/iraakse-kunsten-in-amsterdam/. Zie ook Beeldenstorm; vijf Iraakse kunstenaars in Nederland over hun ervaringen in Irak, ‘Factor’, IKON, Nederland 1, 17 juli, 2003, http://www.ikonrtv.nl/factor/index.asp?oId=924#. Zie over Iraakse kunstenaars uit de Diaspora van verschillende landen (uit Nederland Nedim Kufi) Robert Kluijver, Nat Muller, Borders; contemporary Middle Eastern Art and Discourse, Gemak/ De Vrije Academie, Den Haag, oktober 2007/januari 2009.

[7] Nada Shabout, Shakir Hassan Al Said; A Journey towards the One-dimension, Universe in Universe, Ifa (Duitsland), april, 2008, http://universes-in-universe.org/eng/nafas/articles/2008/shakir_hassan_al_said . Zie ook Saeb Eigner, Art of the Middle East; modern and contemporary art of the Arab World and Iran, Merrell, Londen/New York, 2010; Maysaloun Faraj (ed.), Strokes of genius; contemporary Iraqi art, Saqi Books, Londen, 2002; Mohamed Metalsi, Croisement de Signe, Institut du Monde Arabe, Parijs, 1989. Zie ook hier, op de site van de Darat al-Funun in Amman (Jordanië), een van de meest toonaangevende musea voor moderne en hedendaagse kunst in de Arabische wereld.

[8] Zie mijn interview met Qassim Alsaedy, augustus 2000, gepubliceerd op https://fhs1973.wordpress.com/2008/07/14/. Een interview met Alsaedy in het Arabisch (in al-Hurra) is hier te raadplegen. Zie voor meer werk Qassim Alsaedy’s website, http://www.qassim-alsaedy.com/ of de website van de galerie van Frank Welkenhuysen (Utrecht) http://www.kunstexpert.com/kunstenaar.aspx?id=4481

[9] Patrick Healy, Henk Kraan, Rachid Ben Ali, Amsterdam, 2000; Rudi Fuchs, Het Stedelijk Paleis, de keuze van de Koningin, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam, 2000; Bloothed, Het Domein Sittard, 2003, Rachid Ben Ali, Cobra Museum, Amstelveen, 2005. Zie verder discussie op Maroc.nl (http://www.maroc.nl/forums/archive/index.php/t-43300.html), Premtime (http://www.volkskrant.nl/vk/nl/2844/Archief/archief/article/detail/658197/2005/01/25/PREMtime.dhtml), of bij de Nederlandse Moslimomroep (http://www.nmo.nl/67-kunst__offerfeest_en_nationale_verzoening.html?aflevering=2413).

[10] Dominique Caubet, Margriet Kruyver, Rachid Ben Ali, Thieme Art, 2008. Zie voor recent werk de website van Witzenhausen Gallery, http://www.witzenhausengallery.nl/artist.php?mgrp=0&idxArtist=185

Nedim Kufi en Ahmed Mater; twee bijzondere kunstenaars uit de Arabische wereld nu in Amsterdam – نديم الكوفي وأحمد ماطر

links: Nedim Kufi, News, bedrukt papier op houten latten (detail), 2010 (foto Floris Schreve)

rechts: Ahmed Mater, Waqf Illumination III , Gold Leaf, Tea, Pomegranate, Crystals, Dupont Chinese ink & offset X-Ray film print on paper (detail), 2009

Een weerzien met een oude bekende en een nieuwe ontmoeting

Nedim Kufi en Ahmed Mater; twee toonaangevende en vernieuwende kunstenaars uit de Arabische wereld, nu te zien in Amsterdam

نديم الكوفي وأحمد ماطر

Vanaf 21 mei is er in Amsterdam een bijzondere tentoonstelling te bewonderen, van een aantal vooraanstaande kunstenaars uit het Midden Oosten. Samensteller is Robert Kluijver, die sinds de afgelopen jaren zeer actief is geweest op het gebied van kunst uit het Midden Oosten. Ik geef hier de details:

http://www.baarsprojects.com/index.html

Tot zover de omschrijving van de tentoonstelling. Ik kan trouwens de gehele expositie van harte aanbevelen, er is veel interessant werk te zien. In dit verband wil ik mij richten op twee van de deelnemende kunstenaars, Nedim Kufi en Ahmed Mater. Ik zal ook ingaan op eerder en ander werk, dat niet op deze tentoonstelling is te zien. De anderen, de kunstenaars Rana Begum, Abdulnasser Gharem, Susan Hefuna en Shahzia Sikander bewaar ik wellicht voor een andere gelegenheid.

Nedim Kufi – نديم الكوفي

Nedim Kufi, afkomstig uit Irak, is een van de kunstenaars die ik nog ken van mijn scriptie-onderzoek. Ook in latere artikelen (zoals hier en hier ) heb ik aandacht aan hem besteed. Ook is hij een keer uitgebreid door de NRC geïnterviewd, voor een artikel dat grotendeels over mijn onderzoek naar kunstenaars uit Irak in Nederland ging, zie hier op dit blog. Een tijdje was hij wat uit mijn netwerk verdwenen, al volgde ik hem wel op afstand, vooral via internet. Hoewel hij betrekkelijk weinig in Nederland heeft geëxposeerd is vooral in het buitenland zijn ster steeds meer gaan rijzen. Ook zijn werk heeft in de afgelopen tijd een indrukwekkende ontwikkeling doorgemaakt.

Nedim Kufi, die in het verleden ook bekend stond onder de namen Nedim Muhsen of Nedim El Chelaby, werd in 1962 geboren in Bagdad. Hij studeerde begin jaren tachtig aan de kunstacademie in Bagdad bij de beroemde kunstenaars Ismail Fattah al-Turk (beeldhouwkunst/keramiek) en grafische technieken bij Rafa al-Nasiri. Over zijn tijd aan de academie verklaarde hij het volgende:

‘I applied to the Institute of Fine Arts Baghdad, I was excited, and anxious at the same time about the racist oppression of the Baath Party. While learning and practicing my art, that was also an unpleasant period of my life. You cannot imagine, great depression, no freedom, no oxygen at all’

Na zijn academietijd werd Kufi direct naar het front gestuurd om als soldaat te dienen in de oorlog tegen Iran. Kufi:

‘Although I felt very fortunate to have had art as an alternative companion, sketching up the way I lived in one notebook, it’s also important to include here my emotions. I cannot describe at this moment how much sorrow I carried. I graduated after five years and it was then compulsory for me to become a soldier. Imagine that, during the war with Iran: a black comedy. Counting time until the sun rises and gains in intensity, suddenly one day on 08.08.1988 it was proclaimed that the war was over. Oh my God. I felt I could fly. I needed to make a big difference in my life after this war. But how? How do I escape? I felt fenced into the country. The dream of moving abroad infiltrated my mind every single moment. All of that was a dark layer’.

Uiteindelijk lukte het Kufi om Irak te ontvluchten en na een bizarre omzwerving (over zelfs meerdere continenten) kon hij zich in Nederland vestigen. Sinds die tijd woont en werkt hij in Amersfoort. Ook volgde hij hier nog een opleiding grafische vormgeving aan de Hoge School voor de Kunsten in Utrecht.

Nedim Kufi, Brainwash; Object topical Iraqi, installatie/ready-made, Aleppo-zeep en aluinsteen, 1999

Waarin Kufi zich al vanaf eind jaren negentig van de meeste van zijn in Nederland wonende Iraakse collega’s onderscheidde was het sterke conceptuele karakter van zijn werk. Een van de meest sprekende werken uit die tijd is zijn readymade Brainwah; object toppical Iraqi uit 2001. Te zien is een blokje Aleppo-zeep en een stukje aluinsteen (een soort puimsteen), attributen die in het Midden Oosten tot de vaste bad- assecoires behoren. Alleen doet de vorm van de steen ook denken aan een hersenkwab. Het is de combinatie van de objecten en de titel die het werk een mogelijke betekenis geven. Dit soort dubbelzinnigheden zijn typerend voor het werk van Kufi.

Kufi eerder over dit werk in NRC Handelsblad in 2003 (zie ook op dit blog ): ‘Gewassen hersenen worden van steen – ze slibben dicht, er kan niets meer in’

Nedim Kufi, Eyes everywhere, krijt en potlood op papier, 1999

Een vergelijkbare associatie roept de tekening Eyes everywhere op. Te zien is weer een vorm die sterk doet denken aan een menselijk brein. Alleen is er met potlood op verschillende plaatsen telkens weer hetzelfde tekentje aangebracht. Het gaat hier om de Arabische letter ع (‘ayn), wat ‘oog’ betekent (عين). Het gegeven van ‘overal ogen’, al dan niet ingebeeld, is ook weer een teken waarmee je verschillende kanten op kunt.

Een andere readymade uit dezelfde periode is een enveloppe. Kufi heeft dit werk de titel Brainwash II gegeven. Wellicht gaat het hier om een uit Irak verzonden brief, gericht aan Kufi en gestuurd naar een adres in Borculo (wellicht nog de vluchtelingenopvang). De inhoud van de enveloppe laat zich raden, maar Kufi geeft hier wel een aanwijzing in welke richting wij het moeten zoeken.

Nedim Kufi, Brainwash II, readymade, 1999

Een zelfde soort ironie blijkt ook uit verschillende korte tekstjes, die Kufi een aantal jaren terug op zijn website publiceerde. Hier een passage uit ‘The defenition of Cool’:

‘How do I describe the word C O O L? How come? It’s hard to answer this

question in a couple of pages. But one thing could be very helpful, and that

is everybody nowadays almost says (cool), obviously as an immediate

expression. No need to make the idea of cool explicit any more. It’s an

attitude of this age, a new common language used with the meaning of

superiority and high quality. Yes it has a magic power when it touches

people, I don’t know really! Is it so cool? Is it so attractive? Is it a bit sharp?

Is it too glossy? Or could it be too perfect? It’s logical if life had totally

changed, from age to age (groovy) transformed into (cool) deep into

Internet TITLES mostly extended to (cool) to be saleable items.’

Vervolgens komt hij met een heleboel voorbeelden, zoals:

‘Getting the best model of mobile telephone with special extra function is so cool, Dancing

the whole Saturday night is cool too, Vacation in IBIZA is extremely cool,

Getting your own domain name in www is so cool, Bombing here and there

is very cool, American action movies are so cool, If you win a million is real

cool, If you get a USA passport is cool,’

enz.

Hoewel de tragiek nooit ver weg is, heeft Kufi altijd oog voor het absurde en is zijn werk zeker niet gespeend van enige humor.

Nedim Kufi, ‘Habibi-project’ ( حبيبي = ‘Habibi’) , Amersfoort, 2009

Kufi zet alle mogelijke materialen zoals kauwgum, rozenblaadjes of zeep. In mijn gesprek met Kufi uit 2001 sprak hij dan ook van ‘junk art’. Tegelijkertijd is hij ook bijzonder bedreven in alle mogelijke grafische technieken, tot en met allerlei computeranimaties. Zie bijvoorbeeld zijn Habibi-project dat hij in 2009 in Amersfoort realiseerde, samen met de dichter Gerard Beentjes. ‘Habibi’ betekent overigens ‘mijn liefje’ in het Arabisch. (zie http://www.deweekkrant.nl/files/pdfarchief/AB/20090708/NUC_ANU-1-07_090708_1.pdf )

In zijn recentere werk ontpopt Kufi zich tot een soort alchemist. Aan de Libanese Dayly Star vertelde Kufi dat hij zich opeens een vriend van zijn vader uit zijn kindertijd herinnerde, die werkte als traditionele ‘attar’ (alchemist). Kufi hierover:

“If we say art is a profession only, then it is not enough for me. I mean, I know art is a profession but it has to be more than that. I have to find in art a temple, a ritual, spiritual behavior. So in general, I behave in art as an attar to feel comfortable and complete. From that moment, I feel very much settled.”

Nedim Kufi, Milk, honey, ink and soil, mixed media/installatie (New York, The Phatory Garden of Eden), 2003

Het gegeven van de alchemist lijkt bijna letterlijk te worden in een kleine installatie uit 2003, die Kufi in New York exposeerde (zie bovenstaande afbeelding) Maar ook andere in werken (zie de voorbeelden hiervoor) blijkt in Kufi zich een alchemist, die met ogenschijnlijk waardeloze materialen, of alledaagse beelden, onverwachte schoonheid kan creëren. Kufi is dat in de afgelopen jaren tot en met nu blijven doen, zie de hieronder getoonde voorbeelden waarin hij onder meer werkt met wegwerpmateriaal als zeep en kauwgum. Zie overigens ook dit boeiende interview met Kufi door zijn collega-kunstenaar Ali Mandalawi in al-Sharq al-Awsat in het Arabisch. Daar gaat Kufi uitgebreid in op ‘zijn rol als alchemist’. Kufi zegt ondermeer, dat hij, toen hij in New York exposeerde (zie bovenstaande afbeelding), meermalen de vraag kreeg toegeworpen: ‘Ben u kunstenaar of chemicus?’ Kufi antwoordt dat hij zich als kunstenaar sterk kan identificeren met de traditionele ‘attar’ (of chemicus). Zijn atelier is zijn laboratorium en hij ziet voor de kunst een belangrijke taak weggelegd. Net als de traditionele attar moet de kunstenaar ook het geweten van de samenleving zijn, die het ‘besturingssysteem’ van de maatschappij de juiste richting wijst (hij maakt de vergelijking met het besturingssysteem van een computer). Verder zegt hij in het interview dat het hem opviel dat, itt in Nederland, hem in Amerika vaker werd gevraagd ‘Waar gaat u naartoe?’, dan ‘Waar komt u vandaan?’ Voor hem is de eerste vraag veel wezenlijker dan de tweede.

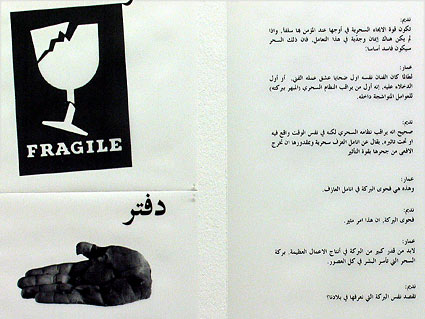

Een tijd lang heeft Kufi ook op internet een soort dagboek bijgehouden, zijn ‘Daftar Project’ (‘Daftar’ betekent ‘schrift’, of ‘notitieboek’ in het Arabisch). Helaas staat dat niet meer online, maar ik geef hieronder het een en ander aan documentatie en afbeeldingen. De twee beelden waarmee hij zijn ‘dagboek’ introduceert en de toeschouwer binnenleidt zijn haast iconisch; een waarschuwing dat het breekbaar is, maar wel met een uitgestoken hand.

http://universes-in-universe.org/eng/nafas/node_60/2006/node_577/photos/kufi_1/

http://web.me.com/southproject/south/Daftar.html

Drie bovenstaande afbeeldingen: Nedim Kufi, Daftar, online schetsboek/dagboek, 2004-2005

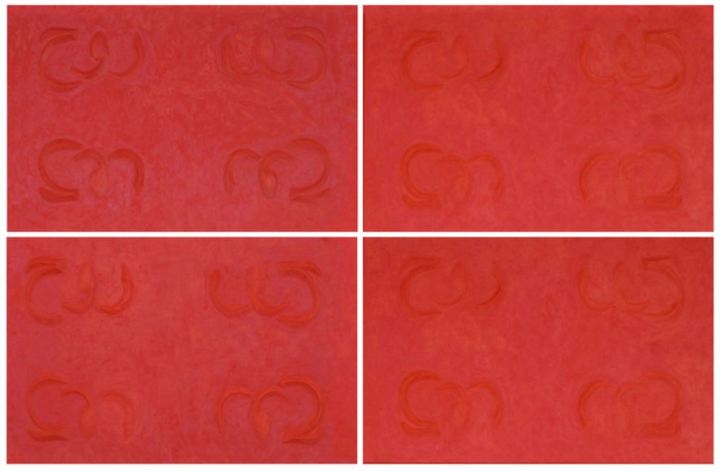

Nedim Kufi, bijdrage aan Dafatir (‘Iraqi Notebook project’), zeventien Iraakse kunstenaars wereldwijd, coördinatie Nada Shabout (University of North Texas), 2006. Zie hier de verschillende bijdragen en hier wat achtergrondinformatie

In 2006 participeerde Kufi in het zg Dafatir-project, een initiatief van de Amerikaanse Iraakse Nada Shabout, hoogleraar hedendaagse kunst van het Midden Oosten aan de Universiteit van North Texas. Zeventien Iraakse kunstenaars, verspreid van over de hele wereld, namen hieraan deel, waaronder grote namen van de iets oudere generatie als Dhia Azzawi, Rafa al-Nasiri en Hanna Mal Allah, maar ook Kufi’s generatie-genoten als Mohamed al-Shammerey. De meeste kunstenaars excelleerden in hun persoonlijke handschrift op miniatuurformaat. De vaak beeldschone resultaten van dit project zijn hier te bekijken. Kufi’s bijdrage was, geheel in zijn stijl, conceptueel en minimalistisch en behoeft eigenlijk geen toelichting, zie bovenstaande afbeelding.

Nedim Kufi, The Moon follows us, gemengde technieken op doek, 2008 (Sultan Gallery, Kuwayt, zie hier voor meer achtergronden)

“On a summers day traveling from Baghdad to Kufa on a visit to relatives the view shifted along our course seducing us. I remember sleeping deeply during this two hour trip, a long time for a child of six. In between sleep I caught sight of the view through the car window; the moon centered in an ecstatic sky. The speeding car followed it through the dark and desolate desert. I was amazed that whenever the car stopped or slowed down so did the moon. It entered my mind freely stirring my astonishment and curiosity, this phenomena, and I asked my father “Oh father…the moon follows us, why is this?” I wished to impress my father with the depth of this phenomenological thought! He smiled but didn’t offer any words in reply. It was as if he had known the answer at a time past, but no longer. The question remained silently with me through out the long night spent with my relatives till we went onto the roof of the house to sleep. There was the moon again reclining above and seeming to own the sky here as it did in Baghdad. With a new sense of clarity I said to my father “this proves my theory, look just as I told you…the moon follows us! Content I fell asleep with a smile… unfortunately the heads of the households seemed only to speak about life’s problems…not paying attention to the moon.

And here I am, unexpectedly passing through the fortieth year of my life, still in a state of surprise. When I try and unravel the darkness and find order in the Dutch sky Baghdad’s moon does not provide sense though it follows me yet softening my estranged and desolate path.” Van http://www.infocusdialogue.com/interviews/nedim-kufi/

Nedim Kufi, Soap and Silence, zeep en tekstiel op paneel, 2008

Nedim Kufi, Rooh/Soul (روح = ziel), rode zeep op doek, 2010

Nedim Kufi, Bore, print op doek, 2009

Nedim Kufi, Nass (ناس = mensen), fotoprint op doek, 2010 (detail)

Nedim Kufi, 20 years later, installatie, 2010

Nedim Kufi, Home/Empty, digitale print, 2008

In Kufi’s meest recente werk keert het thema van zijn ballingschap weer sterk terug. Zie bijvoorbeeld zijn werk 20 years later, waarin hij een vliegticket van Amsterdam naar Baghrein sterk vergroot op doek heeft afgedrukt.

In een interview uit 2006 met Predrag Pajdic zette Kufi zijn verhouding met zijn geboorteland als volgt uiteen:

Pajdic: ‘I expect this ‘identity recycling’ to be the nucleus of your work. Is it?’

Kufi: ‘Yes, I totally agree with you. Identity and what’s beyond is the point. In terms of meanings modeling. I’m not sure yet whether I’m a pure Iraqi or not, but here I will try to figure out to my self at least how much of an Iraqi I am. Feeling like an alien is not an issue any more. Why? Because it started already, in the early dark time of being home in Baghdad in the ’80s and ’90s, and that badly consumed my soul. I was actually under the Baath Party occupation. Where ever I moved I found a checkpoint asking me for my papers. Me and the government. Me and the authority. Me and the dictatorship. We never trusted each other. Like a daily game between Tom and Jerry.

I still shake, if you can believe me, every time I find myself at any airport, or any police office. Even now I have a Dutch passport: the most acceptable one in the world. Look! and pay attention to the contrast: what I had and what I have today. I’m wondering, is identity an official paper? Is it a continuity in the family tree? Is it an army service duty? Is it the place of birth and death? Is it saying yes to what they decide for you? No! I reject all of those common thoughts and focus only on one. And then I may say: being satisfied on a piece of land where ever it is and sleeping deeply, peacefully there without any of nightmares. That is the real identity. According to my experience, there still is an ID conflict which automatically allows my identity to be recycled. From time to time the mirror of the past follows me but in front of me. It reflects clearly my memories. The sweet and bitter ones. And also it’s able to

observe, compare and manipulate the meaning of it. Trying to find a balance somehow. I used to find myself in betweens: imperfect existence. It has to be, one day, full identity. Art could be an ID. Even a good mother language as well. The identity recycling idea came to me while I was in New York City once.

In order to analyse this conflict, I put all my trust in the tongue and eyes of Iraqi kids. Through a visual essay about traveling between here in the Netherlands and the Middle East. My project aims are to update visual feedback of Iraqi kids (6-14 years). Since 1990 they hold at least double identity. My job is like a postman. Collecting and activating a kind of exchange between their stories. Thoughts and dreams in one historical document by video art’ (http://www.infocusdialogue.com/interviews/nedim-kufi/ ).

Nedim Kufi, Home/Absense (foto Floris Schreve)

Nedim Kufi, News, installatie 2011 (foto Floris Schreve)

Zie ook een statement van dit jaar:

An Art that deletes the memory; 21 years later in exile

Sometimes I see myself as an author more than a visual artist, especially when I intensively think on theoretical level which is very different from visual practices I normally do. This happens when I’m outside my studio. This matter makes me always say that “intellect” is a substantial half of the creation of an image. As for the rest, it is some kind of a vision which goes beyond this world, a path to our soul and one important tool to translate our visual dreams. Day by day, it becomes certain and obvious that producing Art is extremely hard task. Seriously I could say here, after my long experience in the field, that a work of Art will get rid of its impurities then change into light. These kinds of things happen in special times of inspiration. They make my many remarks on papers, sketches and failed documents go to the recycle bin, new pure papier-mâché after cooking, as if we are cooking our thoughts. Yes I assume and think that we are in a virtual kitchen. Let me give you my conclusion: We are recycling our lives, words, forms and art, although we always deny this fact, all the way.

Nedim KUFI

Amsterdam | june 2011

In zijn ‘Home/Absence’ serie (2008-2010) is het gegeven van ballingschap duidelijk aanwezig. In ieder werk uit deze reeks keert steeds hetzelfde motief terug. Aan de linkerkant is steeds een (bewerkte) foto weergegeven uit Kufi’s jeugd, waar hij zelf op staat. Aan de rechterkant is dezelfde foto weergeven maar dan gemanipuleerd en heeft Kufi zichzelf weggetoucheerd. Saeb Eigner, in zijn grote overzichtswerk Art of the Middle East (2010) over deze serie:

‘Iraqi artists have reacted to the suffering of their compatriots with varying degrees of directness. Nedim Kufi has used actual photographs as his startingpoint, manipulating them in order to convey the related themes of bloodshed and loss. Based on a photograph taken more than forty years ago, the pair of canvasses here is suggestive rather than explicit, subtly addressing the theme of innocence betrayed’

Saeb Eigner, Art of the Middle East; Modern and Contemporary Art of the Arab World and Iran, Merell, Londen/New York, 2010, p. 173

Op de tentoonstelling in het Willem Baars Project is een van zijnHome/Empty werken te zien, samen met een kleine installatie News, bestaande uit houten latten, waarin fragmenten van artikelen uit Arabische kranten zijn weergeven (zie afb.)

Nedim Kufi woont en werkt in Amersfoort, maar exposeert voornamelijk in de Arabische wereld.

Kufi’s werk in het Willem Baarsproject (foto Floris Schreve), links: Home/Absense (digitale print, 2010) en rechts: News (papier op houten latten, 2010)

werk van Ahmed Mater op de tentoonstelling in het Willem Baarsproject

Ahmed Mater – أحمد ماطر

Ahmed Mater al-Ziad Aseeri werd in 1979 geboren in Rijal Alma, in het Aseeri-gebied van Saoedi-Arabië. Op zijn negentiende ging hij geneeskunde studeren aan het Abha-College. Tegelijkertijd zette hij zijn eerste stappen op het pad van professioneel kunstenaar in het nabijgelegen al-Meftaha Arts Village, dat was gesticht door de Gouverneur van Aseer, ZKH Prins Khalid al-Faisal, zelf dichter en schilder, om de locale kunstscene te stimuleren.

Zijn werk kreeg voor het eerst internationale aandacht, toen Prins Charles van Engeland, in 2000 op bezoek bij Prins Khalid al-Faisal, kennismaakte met het werk van Mater. Doorslaggevend voor zijn loopbaan was echter een bezoek van de Britse kunstenaar Stephen Stapleton in 2003. Stapleton over zijn ontmoeting:

‘I First met Ahmed at the al-Mefthaha Arts Village in March 2003. He was sitting in the corner of his studio in a white. Ankle-length, painted thawb (long shirt), and was surrounded by a sprawling collection of medical paraphernalia. X-rays, anatomical illustrations and prescription receipts jostled for space ammangst bottles of calligraphy ink, spray paint cans and books on Islamic art.

He told me how his ‘double’ life as a doctor and artist had awakened in him a creative energy and motivation to explore humanity, in an era of religious, political and cultural turmoil. With great excitement he showed me his latest paintings; expressive layers of rich colour painted onto human X-rays, marked with religious symbols and hand written medical notes. “An anatomy of faith in the 21st century”, is how he described them’ (In Stephen Stapleton (ed.), with contributions of Venetia Porter, Ashraf Fayadh, Aarnout Helb, ao, Ahmed Mater, Booth-Clibborn Productions, Abha/London 2010, p. 27)

Stapleton bracht Ahmed Mater ook in contact met Venetia Porter, conservator van Word into Art, de permanente tentoonstelling van hedendaagse kunst uit de islamitische wereld in het British Museum. Zij verwierf meteen X Ray (2003, zie onderstaande afbeelding) voor de collectie. Sinds die tijd kan het werk van Ahmed Mater op een groeiende internationale belangstelling rekenen, met als voorlopig hoogtepunt zijn deelname aan de Biënnale van Venetië dit jaar, aan de tentoonstelling The Future of a Promise , waarin een aantal van de meest prominente kunstenaars van de Arabische wereld van dit moment participeren.

Ahmed Mater, X Ray, Mixed media and x-ray film, 2003 (collectie Word into Art, British Museum), zie http://blog.ahmedmater.com/?p=76

Gedurende de afgelopen tien jaar heeft Mater een indrukwekkend oeuvre ontwikkeld, waarin hij zich voornamelijk heeft geconcentreerd op vier verschillende thema’s (al zijn er sinds kort een paar bijgekomen, waar ik hierna nog wat aandacht aan zal besteden). Deze zijn Illumination, Magnetism, Evolution of Man en Yellow Cow . In dit verband wil ik deze vier thema’s een voor een behandelen, waarbij ik een aantal duidelijke voorbeelden zal laten zien.

Allereerst zijn Illuminations, zijn ‘X-rays’. Ahmed Mater is tot op de dag van vandaag ook werkzaam als arts in een ziekenhuis in Abha. De directe inspiratie haalt hij dan ook uit deze omgeving. Maar het gaat er natuurlijk om wat hij met deze röntgenfoto’s doet. Deze zijn verwerkt in complexe composities, rijk gelardeerd met islamitische ornamenten en symbolen, en soms overladen met gekalligrafeerde teksten.

Aan Venetia Porter lichtte Mater het volgende toe: ‘(this painting) explores the confusion in the identity of mankind in the contemporary world. The X-ray, sitting on top of a deep, layered background of medical text and expressive paint, represents an objective view of the individual, chosen to provoke a familiar response…My approach as a doctor has been evidence based and influenced by a direct experience of the world’ (zie http://ahmedmater.com/artwork/illuminations/resume/venetia-porter-/ ). Juist dat ‘evidence based art’ is voor Mater een belangrijk punt, we zullen het nog tegenkomen bij zijn andere werken.

Ahmed Mater, Illumination I & II, Gold Leaf, Tea, Pomegranate, Dupont Chinese ink & offset X-Ray film print on paper. Let op het handschrift boven en onder beide werken. Hier staat in het Arabisch وقف (‘waqf’= ‘charity’)

Over de hier getoonde Illuminations I & II: ‘They are laid out in exactly the same way as the beginning of a religious text. I have also added the word waqf beneath each. This means charity. Traditionally in religious texts you have two pages, symmetrical in design, containing abstract design. The craftsmen would always spend a great deal of time on these opening pages: they’re the first thing you see. Instead of a traditional geometry I have printed two facing X-ray images of human torsos. I prepared the paper using tea, pomegranate, coffee and other materials traditionally used on these kinds of pages. By using them you ensure that when you come to paint onto the paper it will have an extraordinary luminous quality – the paint will truly shine. And that’ what I want to do with this piece, to illuminate. I am giving light. It’s about two humans in conversation. Us and them, and how this encounter gives light. Dar a luz. So many religions around the world share this concept of giving light, not darkness. It is one religious idea that has reached mankind through many different windows.’ ( http://ahmedmater.com/artwork/illuminations/resume/venetia-porter-/ )

Zijn latere Illuminations zijn complexer en weelderiger van compositie. Mater doet hier het begrip ‘illuminatie’ in de zin van ‘boekverluchtingen’ ruimschoots eer aan. Tegelijkertijd zou je zijn deze verluchtingen kunnen opvatten als een artistieke synthese tussen traditie en moderniteit, of als je wilt, tussen religie en wetenschap.

Ahmed Mater, Waqf Illumination III , Gold Leaf, Tea, Pomegranate, Crystals, Dupont Chinese ink & offset X-Ray film print on paper, 2009. Voor vergrote afbeelding en meer details, klik hier

Ahmed Mater, X-Ray Calligpaphy, offsetprint, 2005

Bij Magnetism, zijn tweede thema is eveneens sprake van een soort synthese tussen wetenschap en religie, wellicht nog uitgesprokener dan in zijn Illuminations. Munten zijn X Rays uit in een weelderige vormentaal, zijn magnetisme-reeks is van een verpletterende eenvoud. Eigenlijk is het een simpele trouvaille, waarin met een eenvoudige handeling een heleboel gezegd wordt.

Het enige wat Mater doet is het plaatsen van een magneetblokje in een hoopje ijzervijlsel, met de negatieve pool naar beneden. Het gevolg is dat het ijzervijlsel wordt afgestoten en in een cirkelvormige ring in een regelmatig patroon (vanwege de aantrekkingskracht van de positieve pool aan de bovenkant) blijft liggen. Deze simpele handeling levert de volgende bijna archetypische beelden op (zie onderstaande afbeeldingen):

Het beeld van de vierkanten of rechthoekige magneet, omringd met een cirkel van metaalgruis, roept natuurlijk ook de associatie op met de Kaäba in Mekka, het hart van de islam. Tim Mackintosh-Smith over deze trouvaille (want dat is het eigenlijk):