My Beautiful Enemy; Farhad Foroutanian & Qassim Alsaedy (exhibition Diversity & Art, Amsterdam)

Flyer/handout exhibition (pdf)

قاسم الساعدي و فرهاد فروتنیان

Farhad Foroutanian and Qassim Alsaedy (photo: Nasrin Ghasemzade)

My Beautiful Enemy – دشمن زیبای من – عدوي الجميل

Farhad Foroutanian & Qassim Alsaedy

Mesopotamia and Persia, Iraq and Iran. Two civilizations, two fertile counties in an arid environment. The historical Garden of Eden and the basis of civilization in the ancient world. But also the area were many wars were fought, from the antiquity to the present.The recent war between Iraq and Iran (1980-1988) left deep traces in the lives and the works of the artists

The artists Qassim Alsaedy (Iraq) and Farhad Foroutanian (Iran) both lived through the last gruesome conflict. Both artists, now living in exile in the Netherlands, took the initiative for this exhibition to reflect on this dark historical event, which marked the recent history of their homelands and their personal lives. Neither Farhad nor Qassim ever chose being eachother’s enemies. To the contrary, these two artists make a statement with ‘My Beautiful Enemy’ to confirm their friendship.

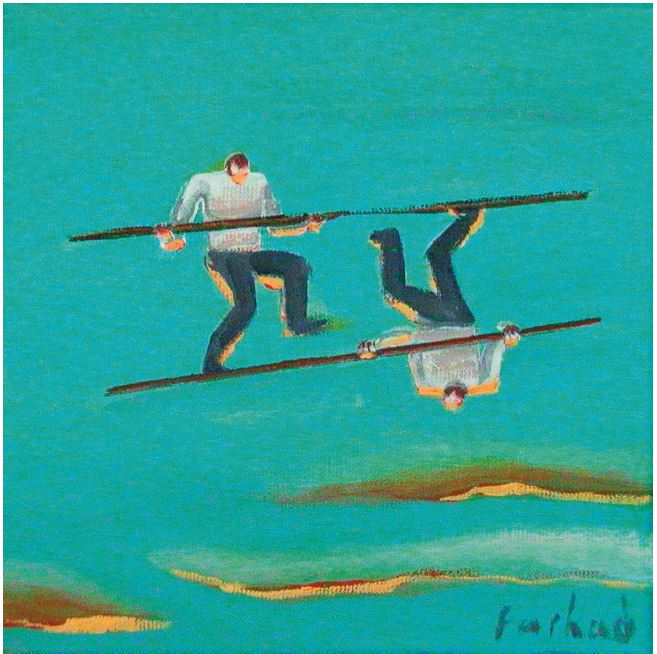

Farhad Foroutanian, Untitled, acrylic on canvas, 2013

Farhad Foroutanian

Farhad Foroutanian (Teheran 1957) studied one and a half year at the theatre academy, before he went to the art academy of Teheran in 1975. At that time the Iranian capital was famous for its hybrid and international oriented art scene. Artists worked in many styles, from pop-art till the traditional miniature painting, a tradition of more than thousand years, in which Foroutanian was trained.

After his education Foroutanian found a job as a political cartoonist at a newspaper. During that time, in 1978, the revolution came, which overthrew the regime of the Pahlavi Shah Dynasty. For many Iranian intellectuals and also for Foroutanian in the beginning the revolution came as a liberation. The censorship of the Shah was dismissed and the revolution created a lot of energy and creativity. A lot of new newspapers were founded. But this outburst of new found freedom didn’t last for long; in the middle of 1979 it became clear that the returned Ayatollah Khomeiny became the new ruler and founded the new Islamic Republic. Censorship returned on a large and villain scale and, in case of the cartoonists, it became clear that they could work as long as they declared their loyalty to the message and the new ideology of the Islamic Republic.

Farhad Foroutanian, Untitled, acrylic on canvas, 2013

The artistic climate became more and more restrictive. In the mid eighties Foroutanian fled his homeland. In 1986 he arrived with his family in the Netherlands. Since that time Foroutanian manifested himself in several ways, as an independent artist, as a cartoonist and as actor/ theatre maker (most of the time together with his wife, the actress Nasrin Ghasemzade Khoramabadi).

Farhad Foroutanian, Untitled, acrylic on canvas, 2013

In his mostly small scaled paintings and drawings Foroutanian shows often a lonely figure of a man, often just a silhouette or a shadow, who tries to deal with an alienating or even surrealistic environment. This melancholical figure, sometimes represented as a motionless observer, sometimes involved in actions which are obviously useless or failing, represents the loneliness of the existence of an exile. Foroutanian:

“If you live in exile you can feel at home anywhere. The situation and location in which an artist is operating, determines his way of looking at theworld. If he feels himself at home nowhere, becomes what the artist produces is very bizarre.

The artist in exile is always looking for the lost identity. How can you find yourself in this strange situation? That is what the artist in exile constantly has to deal with. You can think very rationally and assume that the whole world is your home, but your roots- where you grew up and where you originally belong-are so important.It defines who you are and how you will develop. If the circumstances dictates that you can’t visit the place where your origins are, that has serious consequences. You miss it. You are uncertain if you have ever the chance to see this place again. The only option you have is to create your own world, to fantasize about it. But you can’t lose yourself in this process. You need to keep a connection with the reality, with the here and now. Unfortunately this is very difficult and for some even something impossible. You live in another dimension. You see things different than others ”.

Farhad Foroutanian, Untitled, acrylic on canvas, 2013

In his works the lonely figures are often represented with a suitcase. Foroutanian:

“A case with everything you own in it. Miscellaneous pieces of yourself are packed. And the case is never opened. You carry it from one to another place. And sometimes you open the trunk a little and do something new. But you never open the suitcase completely and you never unpack everything. That’sexile”.

Foroutanian emphasizes that his political drawings were for him personally his anker that prevented him to drift off from reality. The concept of exile is the most important theme in Foroutanian’s work, in his paintings, drawings, but also in his theatre work, like Babel (2007) or No-one’s Land (Niemandsland, 2010). In all his expressions the lonely figure is not far away, just accompanied with his closed suitcase and often long shadow.

Farhad Foroutanian, Untitled, acrylic on canvas, 2013

Foroutanian participated in several exhibitions, in the Netherlands and abroad. He also worked as a cartoonist for some Dutch magazines and newspapers, like Vrij Nederland, Het Algemeen Dagblad and Het Rotterdams Dagblad. Like Qassim Alsaedy he exhibited at an earlier occasion in D&A.

The quotes of Foroutanian are English translations of an interview with the artist in Dutch, by Floor Hageman, on the occasion of a performance of Bertold Brecht’s ‘Der gute Mensch von Sezuan’ (‘ The Good Person of Szechwan’), Toneelgroep de Appel, The Hague, see http://www.toneelgroepdeappel.nl/voorstelling/153/page/1952/Interview_met_Iraanse_cartoonist_Farhad_Foroutanian

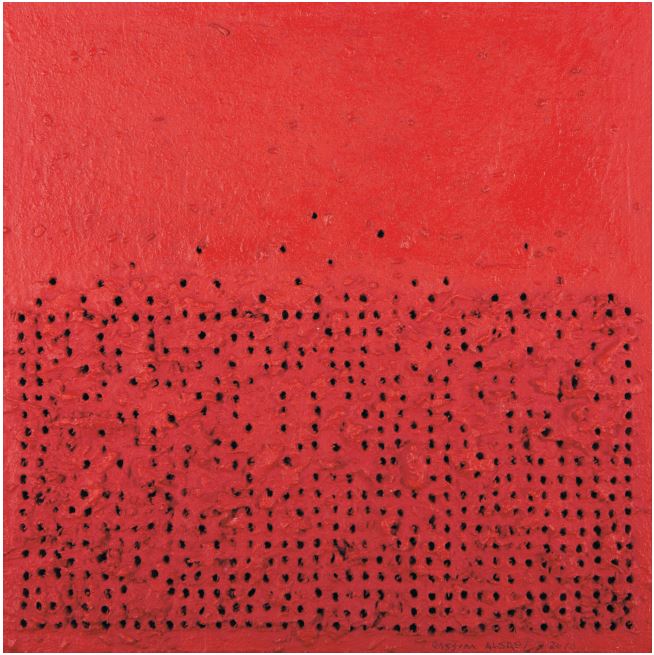

Qassim Alsaedy, untitled, oil on canvas, 2009

Qassim Alsaedy

Qassim Alsaedy (Baghdad 1949) studied at the Academy of Fine Arts in Baghdad during the seventies. One of his teachers was Shakir Hassan al-Said, one of the leading artists of Iraq and perhaps one of the most influential artists of the Arab and even Muslim world of twentieth century. During his student years in the seventies Alsaedy came in conflict with the regime of the Ba’th party. He was arrested and spent nine months in the notorious al-Qasr an-Nihayyah, the Palace of the End, the precursor of the Abu Ghraib prison.

After that time it was extremely difficult for Alsaedy to settle himself as an artist in Iraq. Alsaedy: “Artists who didn’t join the party and worked for the regime had to find their own way”. For Alsaedy it meant he had to go in exile. He lived alternately in Lebanon and in the eighties in Iraqi Kurdistan, where he lived with the Peshmerga (Kurdish rebels). When the regime in Baghdad launched operation ‘Anfal’ , the infamous genocidal campaign against the Kurds, Alsaedy went to Libya, where he was a lecturer at the art academy of Tripoli for seven years. Finally he came to the Netherlands in the mid nineties.

Qassim Alsaedy, untitled, mixed media, 2012/2013

The work of Alsaedy is deeply rooted in the tradition of the Iraqi art of the twentieth century, although of course he is also influenced by his new homeland. The most significant aspect of Alsaedy’s work is his use of abstract signs, almost a kind of inscriptions he engraves in the layers of oil paint in his works. Alsaedy:

“In my home country it is sometimes very windy. When the wind blows the air is filled with dust. Sometimes it can be very dusty you can see nothing. Factually this is the dust of Babylon, Ninive, Assur, the first civilisations. This is the dust you breath, you have it on your body, your clothes, it is in your memory, blood, it is everywhere, because the Iraqi civilisations had been made of clay. We are a country of rivers, not of stones. The dust you breath it belongs to something. It belongs to houses, to people or to some texts. I feel it in this way; the ancient civilisations didn’t end. The clay is an important condition of making life. It is used by people and then it becomes dust, which falls in the water, to change again in thick clay. There is a permanent circle of water, clay, dust, etc. It is how life is going on and on. I have these elements in me. I use them not because I am homesick, or to cry for my beloved country. No it is more than this. I feel the place and I feel the meaning of the place. I feel the voices and the spirits in those dust, clay, walls and air. In this atmosphere I can find a lot of elements which I can reuse or recycle. You can find these things in my work; some letters, some shadows, some voices or some traces of people. On every wall you can find traces. The wall is always a sign of human life”.

Qassim Alsaedy, untitled, mixed media, 2012/2013

The notion of a sign of a wall which symbolizes human life is something Alseady experienced during his time in prison. In his cell he could see the marks carved by other prisoners in the walls as a sign of life and hope.

Later, in Kurdistan, Alsaedy saw the burned landscapes after the bombardments of the Iraqi army. Alsaedy:

“ Huge fields became totally black. The houses, trees, grass, everything was black. But look, when you see the burned grass, late in the season, you could see some little green points, because the life and the beauty is stronger than the evilness. The life was coming through. So you saw black, but there was some green coming up. For example I show you this painting which is extremely black, but it is to deep in my heart. Maybe you can see it hardly but when you look very sensitive you see some little traces of life. You see the life is still there. It shines through the blackness. The life is coming back”.

Qassim Alsaedy, untitled, mixed media, 2012/2013

Another important element in Alsaedy’s mixed media objects is his use of rusted nails or empty gun cartridges. For Alsaedy the nails and the cartridges symbolize the pain, the human suffering and the ugliness of war. But also these elements will rust away and leave just an empty trace of their presence. Life will going on and the sufferings of the war will be once a part of history.

His ceramic objects creates Alsaedy together with the artist Brigitte Reuter. Reuter creates the basic form, while Alsaedy brings on the marks and the first colors. Together they finish the process by baking and glazing the objects.

Qassim Alsaedy, untitled, mixed media, 2012/2013

Since Alsaedy came to the Netherlands he participated in many exhibitions, both solo and group. His most important were his exhibition at the Flehite Museum Amersfoort (2006) and Museum Gouda (2012). He regularly exhibits in the Gallery of Frank Welkenhuysen in Utrecht.

Floris Schreve, Amsterdam, 2013

My Beautiful enemy

28 April- 26 May 2013

O P E N I N G op zondag 28 april om 16.00uur – deur open om 15.00 uur

door Emiel Barendsen – Programma Director Tropentheater

http://www.diversityandart.com/

Diversity & Art | Sint Nicolaasstraat 21 | 1012 NJ Amsterdam | open: do 13.00 – 19.00 | vr t/m za 13.00 – 17.00

عدوي الجميل

قاسم الساعدي وفرهاد فوروتونيان

يسرنا دعوتكم لحضور افتتاح المعرض المشترك للفنانين قاسم الساعدي ( العراق) وفرهاد فوروتونيان ( ايران ) , الساعة الرابعة من بعد ظهر يوم الاحد الثامن والعشرين من نيسان- ابريل 2013

وذلك على فضاء كاليري دي اند أ

الذي يقع على مبعدة مسيرة عشرة دقائق من محطة قطار امستردام المركزية , خلف القصر الملكي

تفتتح الصالة بتمام الساعة الثالثة

Een kleine impressie van de tentoonstelling (foto’s Floris Schreve):

Opening

Emiel Barendsen (foto Floris Schreve)

Dames en heren, goedemiddag,

Toen Herman Divendal mij benaderde met het verzoek een openingswoord tot u te richten ter gelegenheid van de duo expositie van Qassim Alsaedy en Farhad Foroutanian moest ik een moment stilstaan. Immers, ik ben de man die ruim 35 jaar werkzaam is in de podiumkunsten. Weliswaar altijd de niet-westerse podiumkunsten maar toch…podiumkunsten. Herman vertelde mij toen dat hij graag dit soort gelegenheden te baat neemt om anderen dan de usual suspects hun licht te laten schijnen op de tentoongestelde werken. Mooie gedachte die ik met hem deel.

Als Hoofd Programmering en interim directeur van het helaas opgeheven Tropentheater was ik in de gelegenheid om veel te reizen op zoek naar nieuwe artiesten en producties die wij belangrijk en interessant vonden om aan het Nederlandse publiek voor te stellen. In die queste ben je op zoek naar elementen die aan dat specifieke raamwerk appelleren: nieuwsgierigheid, avontuurlijkheid, vakmanschap en ambachtelijkheid, authenticiteit en identiteit maar bovenal de eigen signatuur van de makers.

Beide kunstenaars hier vertegenwoordigd vertellen ons mede op zoek te zijn naar identiteit, beide zijn gevlucht uit hun moederland , beide delen een gezamenlijk bestaan; een gedwongen toekomst. En identiteit is verworden tot een lastig te hanteren begrip in de Nederlandse samenleving anno nu. Sinds de opkomst van populistische partijen hebben wij de mondvol over dé Nederlandse cultuur en identiteit ; maar waar bestaat die in vredesnaam uit. Ik heb er de canon van Nederland nog een op nageslagen en als je het hebt over kunst en cultuur frappeert de constatering dat het juist de externe influx is geweest – en nog immer is – die ons Nederlands DNA bepaalt. Aan de vooravond van een Koningswisseling constateren we dat na de Duits-Oostenrijkse, Engelse, Franse en Spaanse adel de elite van de nieuwe wereld hun opwachting maakt in de Nederlandse monarchie. De ultieme uiting van globalisering. Argentinië nota bene een land opgebouwd uit door conquistadores verkrachte indianen aangevuld met voor armoe gevluchte Sicilianen, Ashkenazische joden, Duitse boeren , Britse gelukzoekers en nazaten van de Westafrikaanse slaven die – behalve hun ritme – de Rio de la Plata niet mochten oversteken, levert de nieuwe Koningin. Wat is onze Nederlandse identiteit eigenlijk als onze kunsthistorische canon vooral gebouwd is op het –wellicht door pragmatisme ingegeven- asiel dat wij boden aan gevluchte kunstenaars: geen Gouden Eeuw zonder Vlamingen, Hugenoten, Sefardische Joden of Armeniers. ‘Onze’ succesvolste nog levende beeldend kunstenares, Marlene Duma, is van Zuid Afrikaanse oorsprong.

Vanuit mijn vakgebied huldig ik het principe dat men tradities moet begrijpen om het hedendaagse te kunnen duiden. Dit geldt niet alleen voor de podiumkunsten maar in mijn optiek ook voor de beeldende kunst. Traditie als conditio sine qua non voor modernisering.

Over de grenzen kijken betekent vooral eerst jezelf leren kennen; wat vind ik mooi, interessant en vooral waarom? Wat zijn die verhalen die je observeert en hoort en in welke culturele context moet ik die plaatsten?

Je laten leiden door je eigen nieuwsgierigheid levert een grote geestelijke verrijking op.

‘My beautiful enemy’ is de titel van deze expositie en verwijst naar het Irak – Iran conflict uit de jaren tachtig van vorige eeuw. Twee buurlanden gebouwd op de civilisaties en dynastieën die de bakermat van onze beschaving vormen. Een gebied dat een lange geschiedenis van conflicten kent maar waar de culturele overeenkomsten groter blijken te zijn dan de verschillen. In samenlevingen waarin de kunstenaar de mond gesnoerd wordt en waar kritische noten niet meer gehoord mogen worden rest vaak maar één pijnlijke optie: ballingschap. Huis en haard worden verlaten om elders in de wereld een nieuw bestaan op te bouwen. Dit proces is voor iedere balling moeilijk en eenzaam; de geschiedenis verankerd in je geheugen is de basis waar je op terugvalt. Mijmeringen over kleuren, geuren, geluiden en smaken van je geboortegrond bijeengehouden door verhalen.

En dat zie je terug in de hier tentoongestelde werken: als ik de werken van Qassim Alsaedy observeer dan herken ik de vakman die in een beeldende taal abstracte verhalen vertelt die een appèl doen op zijn geboortegrond. Als ik mijn ogen luik verbeeld ik mij het landschap te ruiken en hoor ik bij het ene werk de zanger Kazem al Saher op de achtergrond en bij het andere poëtische werk de oud-speler Munir Bachir zachtjes tokkelen.

Farhad Foroutanian gebruikt een ander idioom en zijn stijl verraadt zijn achtergrond als cartoonist. In ogenschijnlijk een paar klare lijnen zet hij zijn figuren neer in een welhaast surreëel decorum. De man met de koffers doet mij terugdenken aan mijn eigen jeugd die ik doorbracht in Zuid-Amerika. Toen aan de vooravond van de gruwelijke Pinochet-coup in Chili de dreiging alsmaar toenam zetten mijn ouder twee koffers klaar waarin de meest noodzakelijke spullen zaten om eventueel te moeten vluchten. Paspoorten en baar geld, kleding en toiletartikelen. Wij moesten niet vluchten, gelukkig, maar werden wel verzocht het land te verlaten. Onze nieuwe bestemming werd het door een burgeroorlog geteisterde Colombia en hoewel dat geweld voornamelijk in de jungle ver van de grote steden plaatsvond waren er momenten dat dat geweld angstig dichtbij kwam. En weer stonden die twee koffers onder handbereik.

Zo blijkt dat deze werken prikkelen en vragen stellen. Het is aan het individu echter om daar invulling aan te geven . Daarover te praten met anderen levert vanzelf weer nieuwe verhalen op.

In een tijd waarin de overheid net doet of diversiteit niet meer van deze tijd is en moedwillig aanstuurt op ondubbelzinnige eenvormigheid ben ik blij dat er nog een plek in Amsterdam is waar men deze prachtige kunst kan aanschouwen.

Ik besluit met het motto “tegenwind is wat de vlieger doet stijgen” en wens Qassim en Farhad alle goeds toe. En u als publiek veel kijkgenot.

Dank u.

Emiel Barendsen

Farhad Foroutanian en Qassim Alsaedy (foto Floris Schreve)

In Front (left): Qassim Alsaedy, the Dutch/Iraqi Kurdish writer Ibrahim Selman and the actress Nasrin Ghasemzade (the wife of Farhad Foroutanian)

Bart Top, Farhad Foroutanian and Ishan Mohiddin

The Iraqi Kudish artists Hoshyar Rasheed and Aras Kareem (who exhibited in D&A before, see here and here), Ishan Mohiddin and Jwana Omer (the wife of Aras Kareem)

De Volkskrant (vrijdag 3 mei 2013):

leave a comment