» Dassault Mirage F1 van de Libische luchtmacht op het luchthaven van Malta AFP

» Dassault Mirage F1 van de Libische luchtmacht op het luchthaven van Malta AFPToegevoegd: maandag 21 feb 2011, 18:15

Update: maandag 21 feb 2011, 23:10

For the english version ‘Modern and contemporary art of the Middle East and North Africa’ click here

Tekst van mijn ingezonden stuk in Kunstbeeld van vorige maand, maar hier voorzien van beeldmateriaal en van een groot aantal links in de tekst, die verwijzen naar diverse sites van de kunstenaars, achtergrondartikelen of documentaires. Overigens geef ik op dinsdag 17 mei een lezing over precies dit onderwerp, in Diversity & Art, Sint Nicolaasstraat 21, Amsterdam, om 20.00, bij de tentoonstelling van Qassim Alsaedy, zie http://www.diversityandart.com/centre.htm (zie over de tentoonstelling het vorige artikel op dit blog). Onderstaande tekst kan ook als introductie dienen op wat ik daar veel uitgebreider aan de orde laat komen:

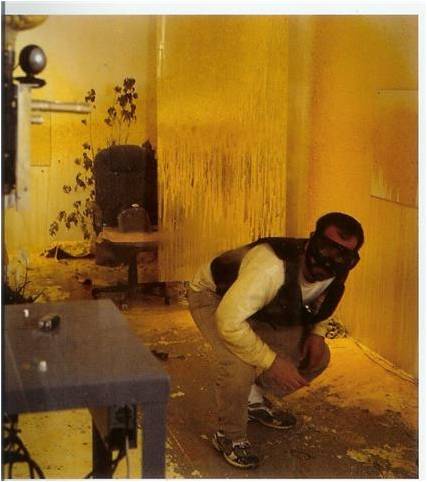

Wafaa Bilal (Iraq, US), from his project ’Domestic Tension’, 2007 (see for more http://wafaabilal.com/html/domesticTension.html )

Hedendaagse kunst uit het Midden Oosten verdient onze aandacht

(in Kunstbeeld, nr. 4, 2011)

Door de recente ontwikkelingen in Tunesië en Egypte en wellicht nog in andere Arabische landen, dringt nu tot de mainstream media door dat er ook in de Arabische wereld en Iran een verlangen naar vrijheid en democratie bestaat. Hoewel in de westerse wereld vaak teruggebracht tot essentialistische clichés, blijkt het beeld van de traditionele Arabier, of de fanatieke moslim vaak niet te kloppen. Het oriëntalistische paradigma, zoals Edward Said het in 1978 heeft omschreven, of zelfs de ‘neo-oriëntalistische’ variant (naar Salah Hassan), die we kennen sinds 9/11, inmiddels ook virulent aanwezig in de Nederlandse politiek, wordt door de beelden van de Arabische satellietzenders als Al Jazeera ontkracht. Er zijn wel degelijk progressieve en vrijheidslievende krachten in het Midden Oosten actief, zoals iedereen nu zelf kan zien.

Pas sinds de laatste jaren begint er steeds meer aandacht te komen voor de hedendaagse kunst uit die regio. Kunstenaars als Mona Hatoum (Palestina), Shirin Neshat (Iran) en de architecte Zaha Hadid (Irak) waren al iets langer zichtbaar in de internationale kunstcircuits. Sinds de afgelopen vijf à tien jaar zijn daar een aantal namen bijgekomen, zoals Ghada Amer (Egypte), Akram Zaatari en Walid Ra’ad (Libanon), Emily Jacir (VS/Palestina) en Fareed Armaly (VS/Palestijns-Libanese ouders), Mounir Fatmi (Marokko), Farhad Mosheri (Iran), Ahmed Mater (Saudi Arabië), Mohammed al-Shammerey en Wafaa Bilal (Irak). Het gaat hier overigens vooral om kunstenaars die tegenwoordig in de westerse wereld wonen en werken.

Walid Ra’ad/The Atlas Group (Lebanon), see http://www.theatlasgroup.org/index.html, at Documenta 11, Kassel, 2002

Mounir Fatmi (Morocco), The Connections, installation, 2003 – 2009, see http://www.mounirfatmi.com/2installation/connexions01.html

Toch is het verschijnsel ‘moderne of hedendaagse kunst’ in het Midden Oosten niet iets van de laatste decennia. Vanaf het eind van de Eerste Wereldoorlog, toen de meeste Arabische landen in de huidige vorm ontstonden, trachtten kunstenaars in diverse landen een eigen vorm van het internationale modernisme te creëren. Belangrijke pioniers waren Mahmud Mukhtar (vanaf de jaren twintig in Egypte), Jewad Selim (jaren veertig en vijftig in Irak), of Mohammed Melehi en Farid Belkahia (vanaf de jaren zestig in Marokko). Deze kunstenaars waren de eerste lichting die, na veelal in het westen waren opgeleid, het modernisme in hun geboorteland introduceerden. Sinds die tijd zijn er in de diverse Arabische landen diverse locale kunsttradities ontstaan, waarbij kunstenaars inspiratie putten uit zowel het internationale modernisme, als uit tradities van de eigen cultuur.

Shakir Hassan al-Said (Iraq), Objective Contemplations, oil on board, 1984, see http://universes-in-universe.org/eng/nafas/articles/2008/shakir_hassan_al_said/photos/08

Ali Omar Ermes (Lybia/UK), Fa, Ink and acryl on paper

Dat laatste was overigens niet iets vrijblijvends. In het dekolonisatieproces namen de kunstenaars vaak expliciet stelling tegen de koloniale machthebber. Het opvoeren van locale tradities was hier veelal een strategie voor. Ook gingen, vanaf eind jaren zestig, andere elementen een rol spelen. ‘Pan-Arabisme’ of zelfs het zoeken naar een ‘Pan-islamitische identiteit’ had zijn weerslag op de kunsten. Dit is duidelijk te zien aan wat de Frans Marokkaanse kunsthistoricus Brahim Alaoui ‘l’ Ecole de Signe’ noemde, de school van het teken. De van zichzelf al abstracte kalligrafische en decoratieve traditie van de islamitische kunst, werd in veel verschillende varianten gecombineerd met eigentijdse abstracte kunst. De belangrijkste representanten van deze unieke ‘stroming’ binnen de moderne islamitische kunst waren Shakir Hassan al-Said (Irak, overleden in 2004), of de nog altijd zeer actieve kunstenaars Rachid Koraichi (Algerije, woont en werkt in Frankrijk), Ali Omar Ermes (Libië, woont en werkt in Engeland) en Wijdan Ali (Jordanië).

Laila Shawa (Palestine), Gun for Palestine (from ‘The Walls of Gaza’), silkscreen on canvas, 1995

Wat wel bijzonder problematisch is geweest voor de ontwikkeling van de eigentijdse kunst van het Midden Oosten, zijn de grote crises van de laatste decennia. De dictatoriale regimes, de vele oorlogen of, in het geval van Palestina, de bezetting door Israël, hebben de kunsten vaak danig in de weg gezeten. Als de kunsten werden gestimuleerd, dan was dat vaak voor propagandadoeleinden, met Irak als meest extreme voorbeeld (de vele portretten en standbeelden van Saddam Hussein spreken voor zich). Vele kunstenaars zagen zich dan ook genoodzaakt om uit te wijken in de diaspora (dit geldt vooral voor Palestijnse en Iraakse kunstenaars). In Nederland wonen er ruim boven de honderd kunstenaars uit het Midden Oosten, waarvan de grootste groep uit vluchtelingen uit Irak bestaat (ongeveer tachtig). Toch is het merendeel van deze kunstenaars niet bekend bij de diverse Nederlandse culturele instellingen.

Mohamed Abla (Egypt), Looking for a Leader, acrylic on canvas, 2006

In de huidige constellatie van enerzijds de toegenomen afkeer van de islamitische wereld in veel Europese landen, die zich veelal vertaalt in populistische politieke partijen, of in samenzweringstheorieën over ‘Eurabië’ en anderzijds de zeer recente stormachtige ontwikkelingen in de Arabische wereld zelf, zou het een prachtkans zijn om deze kunst meer zichtbaar te maken. Het Midden Oosten is in veel opzichten een ‘probleemgebied’, maar er is ook veel in beweging. De jongeren in Tunesië, Egypte en wellicht andere Arabische landen, die met blogs, facebook en twitter hun vermolmde dictaturen de baas waren, hebben dit zonder meer aangetoond. Laat ons zeker een blik de kunsten werpen. Er valt veel te ontdekken.

Floris Schreve

Amsterdam, februari 2011

Ahmed Mater (Saoedi Arabië), Evolution of Man, Cairo Biënnale, 2008. NB at the moment Mater is exhibiting in Amsterdam, at Willem Baars Project, Hoogte Kadijk 17, till the 30th of july. See http://www.baarsprojects.com/

Tot zover mijn bijdrage in Kunstbeeld. Ik wil hieronder nog een klein literatuuroverzichtje geven van een paar basiswerken, die er in de afgelopen jaren verschenen zijn.

• Brahim Alaoui, Art Contemporain Arabe, Institut du Monde Arabe, Parijs, 1996

• Brahim Alaoui, Mohamed Métalsi, Quatre Peintres Arabe Première ; Azzaoui, El Kamel, Kacimi, Marwan, Institut du Monde Arabe, Parijs, 1988.

• Brahim Alaoui, Maria Lluïsa Borràs, Schilders uit de Maghreb, Centrum voor Beeldende Kunst, Gent, 1994

• Brahim Alaoui, Laila Al Wahidi, Artistes Palestiniens Contemporains, Institut du Monde Arabe, Parijs, 1997

• Wijdan Ali, Contemporary Art from the Islamic World, Al Saqi Books, Londen, 1989.

• Wijdan Ali, Modern Islamic Art; Development and continuity, University of Florida Press, 1997

• Hossein Amirsadeghi , Salwa Mikdadi, Nada Shabout, ao, New Vision; Arab Contemporary Art in the 21st Century, Thames and Hudson, Londen, 2009.

• Michael Archer, Guy Brett, Catherine de Zegher, Mona Hatoum, Phaidon Press, New York, 1997

• Mouna Atassi, Contemporary Art in Syria, Damascus, 1998

• Wafaa Bilal (met Kari Lydersen), Shoot an Iraqi; Art, Life and Resistance Under the Gun, City Lights, New York, 2008 (zie hier ook een voordracht van Wafaa Bilal over zijn boek en project)

• Catherine David (ed),Tamass 2: Contemporary Arab Representations: Cairo, Witte De With Center For Contemporary Art, Rotterdam, 2005

• Saeb Eigner, Art of the Middle East; modern and contemporary art of the Arab World and Iran, Merrell, Londen/New York, 2010 (met een voorwoord van de beroemde Iraakse architecte Zaha Hadid).

• Maysaloun Faraj (ed.), Strokes of genius; contemporary Iraqi art, Saqi Books, Londen, 2002 (zie hier een presentatie van de Strokes of Genius exhibition)

• Mounir Fatmi, Fuck the architect, published on the occasion of the Brussels Biennal, 2008

• Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, Grassroots of the Modern Iraqi Art, al Dar al Arabiya, Bagdad, 1986.

• Liliane Karnouk, Modern Egyptian Art; the emergence of a National Style, American University of Cairo Press, 1988, Cairo

• Samir Al Khalil (pseudoniem van Kanan Makiya), The Monument; art, vulgarity and responsibillity in Iraq, Andre Deutsch, Londen, 1991

• Robert Kluijver, Borders; contemporary Middle Eastern art and discourse, Gemak, The Hague, October 2007/ January 2009

• Mohamed Metalsi, Croisement de Signe, Institut du Monde Arabe, Parijs, 1989 (over oa Shakir Hassan al-Said)

• Revue Noire; African Contemporary Art/Art Contemporain Africain: Morocco/Maroc, nr. 33-34, 2ème semestre, 1999, Parijs (uitgebreid themanummer over Marokko).

• Ahmed Fouad Selim, 7th International Biennial of Cairo, Cairo, 1998.

• Ahmed Fouad Selim, 8th International Biennial of Cairo, Cairo, 2001.

• M. Sijelmassi, l’Art Contemporain au Maroc, ACR Edition, Parijs, 1889.

• Walid Sadek, Tony Chakar, Bilal Khbeiz, Tamass 1; Beirut/Lebanon, Witte De With Center For Contemporary Art, Rotterdam, 2002

• Paul Sloman (ed.), met bijdragen van Wijdan Ali, Nat Muller, Lindsey Moore ea, Contemporary Art in the Middle East, Black Dog Publishing, Londen, 2009

• Stephen Stapleton (red.), met bijdragen van Venetia Porter, Ashraf Fayadh, Aarnout Helb, ea, Ahmed Mater, Booth-Clibborn Productions, Abha/Londen 2010 (zie ook www.ahmedmater.com)

• Rayya El Zein & Alex Ortiz, Signs of the Times: the Popular Literature of Tahrir; Protest Signs, Graffiti, and Street Art, New York, 2011 (see http://arteeast.org/pages/literature/641/

Verder nog een aantal links naar relevante websites van kunstinstellingen, manifestaties, tijdschriften, musea en galleries voor hedendaagse kunst uit het Midden Oosten:

Mijn eigen bijdragen (of waar ik mede een bijdrage aan heb geleverd) elders op het web

Op dit blog:

Iraakse kunstenaars in ballingschap

Drie kunstenaars uit de Arabische wereld

Ziad Haider (begeleidende tekst

tentoonstelling)

Qassim Alsaedy (begeleidende tekst tentoonstelling)

Interview met de Iraakse kunstenaar Qassim Alsaedy

Hoshyar Saeed Rasheed (begeleidende tekst tentoonstelling)

Aras Kareem (begeleidende tekst tentoonstelling)

links naar artikelen en uitzendingen over kunstenaars uit de Arabische wereld

De terugkeer van Irak naar de Biënnale van Venetië

Nedim Kufi en Ahmed Mater; twee bijzondere kunstenaars uit de Arabische wereld nu in Amsterdam

Kunstenaars uit de Arabische wereld in Nederland (Eutopia, 2011)

Zie ook mijn nieuwe Engelstalige blog over oa hedendaagse kunst uit de Arabische wereld On Global/Local Art

Qassim Alsaedy werd in 1949 geboren in Bagdad. Zijn familie kwam oorspronkelijk uit de zuidelijke stad al-Amara, maar was, zoals zo velen in die tijd, naar de hoofdstad vetrokken. Het gezin had zich gevestigd in een huis vlak naast de Jumhuriyya Brug over de Tigris, niet ver van het Plein van de Onafhankelijkheid. Voor Alsaedy’s keuze voor het kunstenaarschap was dit gegeven zeker van belang. Na de revolutie van 1958, toen de door de Britten gesteunde monarchie van de troon werd gestoten, werd er op dit plein een begin gemaakt aan de bouw het beroemde vrijheidsmonument (Nasb al-Huriyya) van Iraks bekendste beeldhouwer Jewad Selim, die tegenwoordig veelal wordt gezien als de belangrijkste grondlegger van de modernistische kunst van Irak. Dit werk, dat in 1962 na de dood van Selim voltooid werd, maakte een grote indruk op Alsaedy. Het vrijheidsmonument van Jewad Selim deed Alsaedy voor het eerst beseffen dat kunst niet alleen mooi hoeft te zijn, maar ook werkelijk iets te betekenen kan hebben.

Ook een expositie van de beroemde Iraakse kunstenaar Shakir Hassan al-Said in het Kolbankian Museum in Bagdad in 1962, maakte grote indruk. Alsaedy besloot om zelf kunstenaar te worden. In 1969 deed hij zijn toelatingsexamen aan de kunstacademie van Bagdad, bij Shakir Hassan al-Said, die uiteindelijk een van zijn belangrijkste docenten zou worden in de tweede fase van zijn opleiding.

In de tijd dat Alsaedy zich inschreef aan de kunstacademie had Irak een roerige periode achter de rug en waren de vooruitzichten bijzonder grimmig. In 1963 had een kleine maar fanatieke nationalistische en autoritaire groepering, de Ba’thpartij, kortstondig de macht gegrepen. In de paar maanden dat deze partij aan de macht was, richtte zij een ware slachting aan onder alle mogelijke opponenten. Omdat de Ba’thi’s zo te keer gingen had het leger nog in datzelfde jaar ingegrepen en de Ba’thpartij weer uit de macht gezet. Tot 1968 werd Irak bestuurd door het autoritaire en militaire bewind van de gebroeders Arif, dat wel voor enige stabiliteit zorgde en geleidelijk steeds meer vrijheden toestond. In 1968 wist de Ba’thpartij echter weer de macht te grijpen, deze keer met meer succes. Het bewind zou aan de macht blijven tot 2003, toen een Amerikaanse invasiemacht Saddam Husayn (president vanaf 1979) van de troon stootte. Toch opereerde de Ba’thpartij aan het begin van de jaren zeventig voorzichtiger dan in 1963 en dan zij later in de jaren zeventig zou doen. In eerste instantie werd het kunstonderwijs met rust gelaten, hoewel daar, precies in de periode dat Alsaedy studeerde, daar geleidelijk aan verandering in kwam.

Links: Qassim Alsaedy met Faiq Hassan (links), begin jaren zeventig

Rechts: Qassim Alsaedy met de kunstenaar Kadhim Haydar, ook een van zijn docenten, begin jaren zeventig (foto’s collectie Qassim Alsaedy)

Zover was het nog niet in 1969. Vanaf de jaren veertig was er in Irak een bloeiende avant-garde beweging ontstaan, vooral geïnitieerd door Jewad Selim en de Bagdadgroep voor Eigentijdse Kunst. Naast de groep rond Jewad Selim was er ook Faiq Hassan (Alsaedy’s belangrijkste docent in zijn eerste jaar) en Mahmud Sabri, wiens radicale avant-gardistische opvattingen zo slecht in de smaak vielen bij de Ba’thpartij, dat hij bijna uit de geschiedschrijving van de Iraakse moderne kunst is verdwenen. Toch waren juist de ideeën van Sabri, die al in de vroege jaren zeventig in ballingschap ging en zich uiteindelijk in Praag vestigde, van groot belang voor Alsaedy’s visie op zijn kunstenaarschap. Van Sabri, die een geheel nieuw artistiek concept had ontwikkeld, het zogenaamde Quantum Realisme,leerde Alsaedy dat de kunstenaar de kunstenaar vooral een verschil kan maken door geheel vrij en onafhankelijk te zijn van welke stroming, ideologie of gedachtegoed dan ook, iets wat hij in zijn verdere loopbaan altijd zou proberen na te streven.

Een andere belangrijke docent van Alsaedy was Shakir Hassan al-Said, een van de beroemdste kunstenaars van Irak en zelfs van de Arabische wereld. Al-Said bracht Alsaedy ook in contact met Jabra Ibrahim Jabra, de beroemde schrijver en kunstcriticus van Palestijnse afkomst, in die dagen een van de belangrijkste figuren binnen de Iraakse kunstscene. Maar verder was de invloed van Shakir Hassan van groot belang op Alsaedy’s artistieke vorming. Na een expressionistische periode had Shakir Hassan al Said een zeer persoonlijke abstracte beeldtaal ontwikkeld, waarbij het Arabische alfabet als basis diende. Ook had al-Said een uitgebreide theorie ontwikkeld, die hij voor zijn werk als uitgangspunt nam. Hijzelf en een aantal geestverwanten vormden de zogenaamde One Dimension Group. Hoewel er misschien iets van een oppervlakkige verwantschap is tussen het werk van Shakir Hassan al-Said en dat van Alsaedy – ook al-Said liet zich vaak inspireren door opschriften op muren en ook veel van zijn werken hebben titels als Writings on a Wall – zijn er ook wezenlijke verschillen. Al-Said en zijn geestverwanten putten vooral inspiratie uit de abstracte islamitische traditie, waarbij zij vooral het Arabisch schrift als uitgangspunt namen. De bronnen van Alsaedy hebben veelal een andere oorsprong, die niet in de laatste plaats samenhangen met een van de meest indringende ervaringen van leven.

Qassim Alsaedy, Rhythms in White, assemblage van dobbelstenen, 1999

Halverwege Alsaedy’s tijd aan de academie werd de controle van de Ba’thpartij, die nog maar net aan de macht was, steeds sterker. Het regime begon zich ook met het kunstonderwijs te bemoeien. Op een geven moment werd Alsaedy, samen met een paar anderen, uitgenodigd door een paar functionarissen van het regime. In 2000 beschreef Alsaedy deze bijeenkomst als volgt: ‘We were invited for a meeting to drink some tea and to talk. They told us they liked to exhibit our works, in a good museum, with a good catalogue and they promised all these works would be sold, for the prize we asked. It seemed that the heaven was open for us. But then they came with their conditions. We had to work according the official ideology and they should give us specific titles. We refused their offer, because we were artists who were faithful towards our own responsibility: making good and honest art. When we agreed we would sold ourselves. (..) Later they found some very cheap artists who were willing to sell themselves to the regime and they joined them. All their paintings had been sold and the prizes were high. One of them, I knew him very well, he bought a new villa and a new car. And in this way they took all the works of these bad artists, and showed them and said: “Well, this is from the party and these are the artists of Iraq”. The others were put in the margins of the cultural life’ (uit mijn Interview met Qassim Alsaedy, 8-8-2000).

Qassim Alsaedy, Saltwall, olieverf op doek, 2005

Alsaedy benadrukt dat bijna zijn hele generatie ‘nee’ heeft gezegd tegen het regime, waarvoor velen een hoge prijs hebben moeten betalen. Alsaedy spreekt dan ook van ‘the lost generation’, waarmee hij specifiek de lichting kunstenaars van de jaren zeventig bedoelt. De kunstenaars van voor die tijd hadden al een carrière voordat het regime zich met de kunsten ging bemoeien en de latere generatie had te maken met kunstinstituties die al geheel waren geïncorporeerd in het staatsapparaat. De problemen waarmee die kunstenaars te maken kregen waren natuurlijk minstens net zo groot, maar van een andere aard, dan de lichting kunstenaars die gevormd werd gedurende de periode van transitie. De generatie van de jaren zeventig zag en ervoer hoe de kunstscene langzaam werd ‘geba’thificeerd’.

Ook was Alsaedy lid van een verboden studentenbond. Dit alles leidde uiteindelijk tot zijn arrestatie. Op een gegeven moment werd Alsaedy midden op de dag opgepakt en afgevoerd naar de meest beruchte gevangenis van Irak van dat moment, al-Qasr al-Nihayyah, ‘het Paleis van het Einde’. Dit was het voormalige Koninklijke Paleis dat in de jaren zeventig door het regime als gevangenis was ingericht, totdat in de jaren tachtig de inmiddels algemeen bekende en beruchte Abu Ghraib open ging.

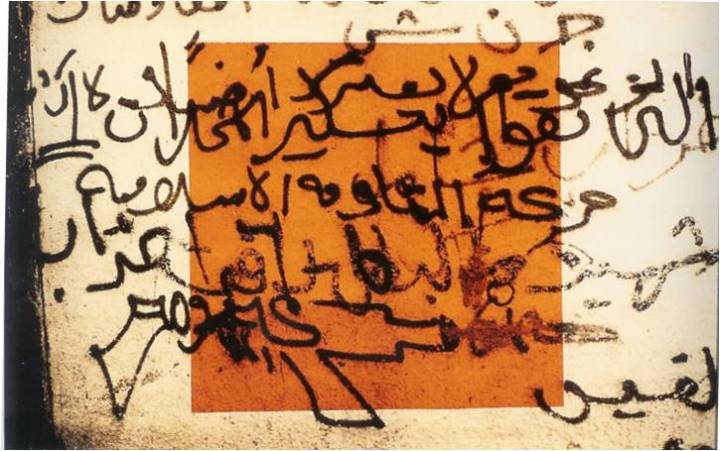

Voor negen maanden ging Alsaedy door de meest intensieve periode van zijn leven. Martelingen en de permanente dreiging van executie waren aan de orde van de dag. Gedurende de negen maanden dat hij zich hier bevond werd Alsaedy teruggeworpen tot zijn meest elementaire bestaan. Zijn omgeving was gereduceerd tot de gevangenismuren. Daar kwam Alsaedy tot een belangrijk inzicht. Hij ontdekte dat de velen die voor hem zich in deze ruimte hadden bevonden kleine sporen van hun bestaan hadden achtergelaten. Op de muren waren ingekraste tekeningen of opschriften zichtbaar, meestal nog maar vaag zichtbaar. Alsaedy kwam tot het besef dat deze tekeningen van de gevangenen de laatste strohalm betekenden om mens te blijven. Zelfs in de donkerste omstandigheden trachtten mensen op de been te blijven door zich te uiten in primitief gemaakte tekeningen of om hun getuigenissen op de muren te krassen. Dit inzicht zou allesbepalend zijn voor Alsaedy’s verdere kunstenaarschap. Het thema ‘krassen of tekens op muren’, de rode draad in zijn hele oeuvre, vond hier zijn oorsprong.

Na deze negen maanden werd Alsaedy, middels een onverwachte amnestieafkondiging, samen met een groep andere gevangenen weer vrijgelaten. Een succesvol bestaan als kunstenaar via de gevestigde kanalen in Irak zat er voor hem niet meer in. Alsaedy werd definitief als verdacht bestempeld en was bij het regime uit de gratie geraakt. Hij besloot zijn heil elders te zoeken en week in 1979 uit naar Libanon. Daar participeerde hij samen met andere uitgeweken Iraakse kunstenaars aan een tentoonstelling die mede een aanklacht was tegen het regime van de Ba’thpartij in Irak.

De onrustige situatie in het Midden Oosten maakte dat Qassim Alsaedy als Iraakse balling altijd op de vlucht moest, om te proberen elders een (tijdelijk) veilig heenkomen te zoeken. Door de burgeroorlog was Libanon een allerminst veilige plek en bovendien voltrokken zich ook nieuwe ontwikkelingen in Irak. Saddam Husayn was inmiddels president geworden en had alle oppositie, zelfs binnen zijn eigen partij, geëlimineerd. Vervolgens had hij zijn land in een bloedige oorlog met Iran gestort. Hoewel de Ba’thpartij met straffe hand het land controleerde, was er in het Koerdische noorden een soort schemergebied ontstaan, waar veel Iraakse oppositiekrachten naar waren uitgeweken. Door de chaotische frontlinies van de oorlog en doordat de Koerden, beter dan welke andere groepering in Irak, zich hadden georganiseerd in verzetsgroepen, was dit een gebied een soort vrijhaven geworden. Alsaedy kwam in 1982 terecht in de buurt van Dohuk, in westelijk Koerdistan en sloot zich, samen met andere Iraakse ‘politiek ontheemden’, aan bij de Peshmerga, de Koerdische verzetsstrijders. Naast dat hij zich bij het verzet had aangesloten was hij ook actief als kunstenaar. Naar aanleiding van deze ervaringen maakte hij later een serie werken, die bedekt zijn met een zwarte laag, maar waarvan de onderliggende gekleurde lagen sporadisch zichtbaar zijn door de diepe krassen die hij in zijn schilderijen had aangebracht.

Qassim Alsaedy, Black Field, olieverf op doek, 1999

Alsaedy over deze werken (zie bovenstaande afbeelding): ‘In Kurdistan I joined the movement which was against the regime. I worked there also as an artist. I exhibited there and made an exhibition in a tent for all these people in the villages, but anyhow, the most striking was the Iraqi regime used a very special policy against Kurdistan, against this area and also against other places in Iraq. They burned and sacrificed the fields by enormous bombings. So you see, and I saw it by myself, huge fields became totally black. The houses, trees, grass, everything was black. But look, when you see the burned grass, late in the season, you could see some little green points, because the life and the beauty is stronger than the evil. The life was coming through. So you saw black, but there was some green coming up. For example I show you this painting which is extremely black, but it is to deep in my heart. Maybe you can see it hardly but when you look very sensitive you see some little traces of life. You see the life is still there. It shines through the blackness. The life is coming back’ (geciteerd uit mijn interview met Alsaedy uit 2000).

Een impressie uit Alsaedy’s atelier, februari 2011

Gedurende bijna de hele oorlog met Iran verbleef Alsaedy in Koerdistan. Aan het eind van de oorlog, in 1988, lanceerde het Iraakse regime de operatie al-Anfal, de grootschalige zuivering van het Koerdische platteland en de bombardementen met chemische wapens op diverse Koerdische steden en dorpen, waarvan die op Halabja het meest berucht is geworden. Voor Alsaedy was het in Irak definitief te gevaarlijk geworden en moest hij zijn heil elders zoeken.

Het werd uiteindelijk Libië. Alsaedy: ‘I moved to Libya because I had no any choice to go to some other place in the world. I couldn’t go for any other place, because I couldn’t have a visa. It was the only country in the world I could go. Maybe it was a sort of destiny. I lived there for seven years. After two years the Kuwait war broke out in Iraq followed by the embargo and all the punishments. In this time it was impossible for a citizen of Iraq to have a visa for any country in the world’ (uit interview met Qassim Alsaedy, 2000).

Hoe vreemd het in de context van nu ook mag klinken, gedurende die tijd leefde Muammar al-Qadhafi in onmin met zo’n beetje alle Arabische leiders, inclusief Saddam Husayn. Het was precies op dat moment in de grillige loopbaan van de Libische dictator, dat hij zijn deuren opende voor alle mogelijke dissidenten van diverse pluimage uit de hele Arabische wereld. Ook Alsaedy kon daar zijn heenkomen zoeken en hij kreeg bovendien een betrekking als docent aan de kunstacademie van Tripoli.

Qassim Alsaedy werkt met zijn studenten in Tripoli aan een speciaal muurschilderingenproject, in 1989 en in 1994 (foto’s collectie Qassim Alsaedy)- klik op afbeelding voor vergrote weergave

In Libië voerde hij ook een groot muurschilderingenproject uit. Tegen zijn eigen verwachting in kreeg hij toestemming voor zijn plannen. Alsaedy: ‘I worked as a teacher on the academy of Tripoli, but the most interesting thing I did there was making many huge wallpaintings. The impossible happened when the city counsel of Tripoli supported me to execute this project. I had always the dream how to make the city as beautiful as possible. I was thinking about Bagdad when I made it. My old dream was to do something like that in Bagdad, but it was always impossible to do that, because of the regime. I believe all the people in the world have the right on freedom, on water, on sun, on air, but also the right on beauty. They have the right on beauty in the world, or in their lives. So one of my aims was to make wallpaintings and I worked hard on it. They were abstract paintings, but I tried to give them something of the atmosphere of the city. It is an Arabic, Islamic city with Italian elements. I tried to make something new when I studied the Islamic architecture. I worked on them with my students and so something very unusual happened, especially for the girls, because in our society it is not very usual to see the girls painting on the street. It was a kind of a shock, but in a nice way. It brought something positive’ (interview met Qassim Alsaedy, 2000).

Toch was ook Libië een politiestaat en zat het gevaar in een klein hoekje. De functionaris van het Libische regime, onder wiens verantwoordelijkheid Alsaedy’s project viel, vond een oranjekleurige zon in een van Alsaedy’s muurschilderingen verdacht. Volgens hem was deze zon eigenlijk rood en zou het gaan om verkapte communistische propaganda (zie bovenstaande afbeeldingen, rechtsonder). Alsaedy werd te kennen gegeven dat hij de zon groen moest schilderen, de kleur van de ‘officiële ideologie’ van het Qadhafi-bewind (zie het beruchte en inmiddels ook hier bekende ‘Groene Boekje’). Alsaedy weigerde dit en werd meteen ontslagen.

Zijn ontslag betekende ook dat Alsaedy’s verblijf in Libië een riskante aangelegenheid was geworden. Hij exposeerde nog wel in het Franse Culturele Instituut, maar had alle reden om zich niet meer veilig te voelen. Hij besloot dat het beter was om met zijn gezin zo snel mogelijk naar Europa te verdwijnen. Uiteindelijk kwam hij in 1994 aan in Nederland.

Vanaf eind jaren negentig, toen Alsaedy na een turbulent leven met vele omzwervingen ook de rust had gevonden om aan zijn oeuvre te bouwen, begon hij langzaam maar zeker zichtbaar te worden in de Nederlandse kunstcircuits. Zijn eerste tentoonstellingen waren vaak samen met zijn ook uit Irak afkomstige vriend Ziad Haider (zie deze eerdere expositie). Met een viertal andere uit Irak afkomstige kunstenaars (waaronder ook Hoshyar Rasheed, zie deze eerdere expositie) exposeerde hij in 1999 in Museum Rijswijk, zijn eerste museale tentoonstelling in Nederland.

In die periode werd de centrale thematiek van Alsaedy’s werk steeds meer zichtbaar. Voor Qassim Alsaedy staan de sporen die de mens in de loop der geschiedenis achterlaat centraal, van de vroegste oudheid (bijvoorbeeld Mesopotamië) tot het recente verleden (zie zijn ervaring in de gevangenis, of de zwarte laag in zijn ‘Koerdische landschappen’).

In 2000 formuleerde hij zijn centrale concept als volgt: ‘When I lived in Baghdad I travelled very often to Babylon or other places, which were not to far from Baghdad. It is interesting to see how people reuse the elements of the ancient civilizations. For example, my mother had an amulet of cylinder formed limestones. She wore this amulet her whole lifetime, especially using it when she had, for example a headache. Later I asked her: “Let me see, what kind of stones are these?” Then I discovered something amazing. These cylinder stones, rolling them on the clay, left some traces like the ancient writings on the clay tablets. There was some text and there were some drawings. It suddenly looked very familiar. I asked her: “what is this, how did you get these stones?” She told me that she got it from her mother, who got it from her mother, etc. So you see, there is a strong connection with the human past, not only in the museum, but even in your own house. When you visit Babylon you find the same traces of these stones. So history didn’t end.

In my home country it is sometimes very windy. When the wind blows the air is filled with dust. Sometimes it can be very dusty you can see nothing. Factually this is the dust of Babylon, Ninive, Assur, the first civilizations. This is the dust you breath, you have it on your body, your clothes, it is in your memory, blood, it is everywhere, because the Iraqi civilizations had been made of clay. We are a country of rivers, not of stones. The dust you breath it belongs to something. It belongs to houses, to people or to some clay tablets. I feel it in this way; the ancient civilizations didn’t end. The clay is an important condition of making life. It is used by people and then it becomes dust, which falls in the water, to change again in thick clay. There is a permanent circle of water, clay, dust, etc. It is how life is going on and on.

I have these elements in me. I use them not because I am homesick, or to cry for my beloved country. No it is more than this. I feel the place and I feel the meaning of the place. I feel the voices and the spirits in those dust, clay, walls and air. In this atmosphere I can find a lot of elements which I can reuse or recycle. You can find these things in my work; some letters, some shadows, some voices or some traces of people. On every wall you can find traces. The wall is always a sign of human life’ (interview met Qassim Alsaedy, 2000).

Qassim Alsaedy, Rhythms, spijkers op hout, 1998

Qassim Alsaedy, uit de serie Faces of Baghdad, assemblage van metaal en lege patroonhulzen op paneel, 2005 (geëxposeerd op de Biënnale van Florence van 2005)

Een opvallend element in Alsaedy’s werk is het gebruik van spijkers. Ook op deze tentoonstelling zijn daar een aantal voorbeelden van te zien. Over een ander werk, een assemblage van spijkers in een verschillende staat van verroesting zei Alsaedy (voor een documentaire van de Ikon uit 2003) het volgende: ‘Dit heb ik gemaakt om iets over de pijn te vertellen. Wanneer de spijkers wegroesten zullen zij uiteindelijk verdwijnen. Er blijven dan alleen nog maar een paar gaatjes over. En een paar kruisjes’ (uit Beeldenstorm, ‘Factor’, Ikon, 17 juni 2003).

Een zelfde soort element zijn de patroonhulzen, die vaak terugkeren in Alsaedy’s werk, ook op deze tentoonstelling. Ook deze zullen uiteindelijk vergaan en slechts een litteken achterlaten.

In een eerder verband heb ik Alsaedy’s werk weleens vergeleken met dat van Armando (bijv. in ISIM Newsletter 13, december 2003). Beiden raken dezelfde thematiek. Toch zijn er ook belangrijke verschillen. In zijn ‘Schuldige Landschappen’ geeft Armando uitdrukking aan het idee dat er op een plaats waar zich een dramatische gebeurtenis heeft afgespeeld (Armando verwijst vaak naar de concentratiekampen van de Nazi’s) er altijd iets zal blijven hangen, al zijn alle sporen uitgewist. Alsaedy gaat van hetzelfde uit, maar legt toch een ander accent. In zijn zwarte werken en met zijn gebruik van spijkers en patroonhulzen benadrukt Alsaedy juist dat de tijd uiteindelijk alle wonden heelt, al zal er wel een spoor achterblijven.

Qassim Alsaedy (ism Brigitte Reuter), Who said no?, installatie Flehite Museum, Amersfoort, 2006

Sinds de laatste tien jaar duikt er in het werk van Alsaedy steeds vaker een crucifix op. Ook op deze tentoonstelling is daar een voorbeeld van te zien. Dat is opmerkelijk, omdat de kunstenaar geen Christelijke achtergrond heeft en ook niet Christelijk is. Alsaedy heeft het verhaal van Jezus echter ontdaan van zijn religieuze elementen. Duidelijk bracht hij dit tot uitdrukking in zijn installatie in het Flehite Museum in Amersfoort, getiteld ‘Who said No?’ Los van de religieuze betekenis, is Jezus voor Alsaedy het ultieme voorbeeld van iemand die duidelijk ‘Nee’ heeft gezegd tegen de onderdrukking en daar weliswaar een hoge prijs voor heeft betaald, maar uiteindelijk gewonnen heeft. Op de manier zoals Alsaedy de crucifix heeft verwerkt is het een herkenbaar symbool geworden tegen dictatuur in welke vorm dan ook.

Detail ‘tegelvloer’ van Qassim Alsaedy en Brigitte Reuter

Gedurende de afgelopen tien jaar heeft Alsaedy veel samengewerkt met de ceramiste Brigitte Reuter. Ook op deze tentoonstelling zijn een aantal van hun gezamenlijke werken geëxposeerd. Gezien Alsaedy’s fascinatie voor het materiaal (zie zijn eerdere opmerkingen over de beschavingen uit de oudheid van Irak) was dit een logische keuze. De objecten zijn veelal door Reuter gecreëerd en door Alsaedy van reliëf voorzien, vaak een zelfde soort tekens die hij in zijn schilderijen heeft verwerkt. Door de klei te bakken, weer te bewerken of te glazuren en weer opnieuw te bakken, ontstaat er een zelfde soort gelaagdheid die ook in zijn andere werken is te zien. Een hoogtepunt van hun samenwerking was een installatie in het Rijksmuseum voor Oudheden in Leiden in 2008. In het Egyptische tempeltje van Taffeh, dat daar in de centrale hal staat, legden zij een vloer aan van gebakken en bewerkte stenen. Maar ook eerder, in het Flehite Museum, waren veel van hun gezamenlijke ‘vloeren’ en objecten te zien.

Uit Book of Time, gemengde technieken op papier, 2001 (detail)

Een ander interessant onderdeel van Alsaedy’s oeuvre zijn zijn tekeningenboekjes. Op deze tentoonstelling is daar een van te bezichtigen, Book of Time, uit 2001. Pagina na pagina heeft hij, als het ware laag over laag, verschillende tekens aangebracht met verschillende technieken (pentekening, inkt, aquarel en collage). Ook hier is zijn kenmerkende ‘tekenschrift’ zeer herkenbaar.

In 2003 werd het Ba’thregime van Saddam Husayn door een Amerikaanse invasiemacht ten val gebracht. Net als op alle in ballingschap levende Iraki’s, had dit ook op Qassim Alsaedy een grote impact. Hoewel zeker geen voorstander van de Amerikaanse invasie en bezetting (zoals de meeste van zijn landgenoten) betekende het wel dat, ondanks alle onzekerheden, er nieuwe mogelijkheden waren ontstaan. En bovenal dat het voor Alsaedy weer mogelijk was om zijn vaderland te bezoeken. In de zomer van 2003 keerde hij voor het eerst terug. Naast

Qassim Alsaedy, object uit ‘Last Summer in Baghdad’, assemblage van kleurpotloden op paneel, 2003

Qassim Alsaedy, Shortly after the War, 2011 (detail)

dat hij natuurlijk zijn familie en oude vrienden had bezocht, sprak hij ook met een heleboel kunstenaars, dichters, schrijvers, musici, dansers en vele anderen over hoe het Iraakse culturele leven onder het regime van Saddam had geleden. Van de vele uren film die hij maakte, zond de VPRO een korte compilatie uit, in het kunstprogramma RAM, 19-10-2003 (hier te bekijken).

In de jaren daarna bleef dit bezoek een belangrijke bron van inspiratie. Alsaedy maakte verschillende installaties en objecten. Vaak zijn in deze werken twee kanten van de medaille vertegenwoordigd, zowel de oorlog en het geweld, maar ook de schoonheid, die eeuwig is en het tijdelijke overwint.

Vanaf halverwege de jaren 2000 is Qassim Alsaedy steeds zichtbaarder geworden in zowel Nederlandse als buitenlandse kunstinstellingen. Vanaf 2003 exposeerde hij regelmatig in de gerenommeerde galerie van Frank Welkenhuysen in Utrecht, waar hij tegenwoordig als vaste kunstenaar aan verbonden is. Ook participeerde hij in de Biënnale van Florence in 2003 en exposeerde hij tweemaal in het Rijksmuseum van Oudheden. Een belangrijk hoogtepunt was zijn grote solotentoonstelling in het Flehite Museum in Amersfoort in 2006.

Met enige trots presenteren wij in Diversity & Art zijn project ‘Shortly after the War’.

Floris Schreve

Amsterdam, april 2011

Qassim Alsaedy bij de inrichting van de tentoonstelling

Diversity & Art | Sint Nicolaasstraat 21 | 1012 NJ Amsterdam| The Netherlands | open: Thursday 13.00 – 19.00 | Friday and Saturday 13.00 – 17.00

Opening on Friday April 22 at 17:30 by Neil van der Linden,

specialist in art and culture of the Arab and Muslim world

(mainly in the field of music and theater)

doors open at 16.30

LectureonTUESDAY,May 17at 20:00byFloris Schreve

“Modern and Contemporary ArtofIraqand the Arab world”

For this occasion Qassim Alsaedy will present his installation of several objects ‘Shortly after the War’. The ceramic objects are created in collaboration with the Dutch/German artist Brigitte Reuter (see http://www.utrechtseaarde.nl/reuter_b.html )

An impression of Alsaedy’s recent work in his studio (February 2011):

See also:

http://www.qassim-alsaedy.com/

http://www.kunstexpert.com/kunstenaar.aspx?id=4481

http://www.diversityandart.com/centre.htm

See also on this blog:

Interview with the Iraqi artist Qassim Alsaedy

In Dutch:

Iraakse kunstenaars in ballingschap

Drie kunstenaars uit de Arabische wereld

links naar artikelen en uitzendingen over kunstenaars uit de Arabische wereld

Denkend aan Bagdad- door Lien Heyting

van International Network of Iraqi Artists (iNCIA), Londen: http://www.incia.co.uk/31293.html.

SOLO EXHIBITION

SOLO EXHIBITION

22 Apr – 28 May 2011

Diversity and Art

Netherlands

Born Baghdad 1949, AlSaedy studied painting at the Academy of Fine Arts in Baghdad from 1969-73. He was a student of the late Shakir Hassan al-Said, one of the most significant and influential artists of Iraq and even the Arab World. During his time at the academy Alsaedy was arrested and imprisoned for almost a year. Free again in1979, he organized with other Iraqi artists an exhibition in Lebanon, as a statement against the Iraqi regime. Back in Iraq, he joined the Kurdish rebels in the North, where he also was active as an artist and even exhibited in tents. After the Anfal campaign against the Kurds in 1988 he withdrew to Libya where he could work in relative freedom and where he became a teacher at the Art Academy of Tripoli until 1994, when he came to the Netherlands. Alsaedy’s work is dominated by two themes, love versus pain and the ongoing cycle of growth and decay, a recycling of material when man leaves his characters and traces as a sign of existence through the course of history. Love is represented by beauty in bright and deep colors. The pain from the scars of war and destruction is visualized by the empty cartridge cases from the battlefield or represented by the rusty nails, an important element in many of his works. “The pain has resolved as the nails are completely rusted away”, states Alsaedy. In his three dimensional work, the duality of pain and beauty is always the main theme. For this occasion Qassim Alsaedy will present his installation of several objects ‘Shortly after the War’. The ceramic objects are created in collaboration with the Dutch/German artist Brigitte Reuter.

Diversity & Art

van http://www.sutuur.com/ar/iraqi-outside/158-qassimalsaedy:

| المعرض الجديد للفنان قاسم الساعدي |

|

بعد الحرب بقليل صياغة جديدة لمعادلة الامل والالم الثاني والعشرون من نيسان الجاري , وعلى صالة كاليري “DIVERSITY & ART ” في امستردام , يفتتح المعرض الشخصي الجديد للفنان قاسم الساعدي , المعنون ب : بعد الحرب بقليل حيث سيعرض فيه مختارات من احدث اعماله, تضم لوحات , نحت , اعمال ثلاثية الابعاد, مخطوطة كتاب, وبعض قطع السيراميك التي انجزها الفنان بالتعاون مع الفنانة الالمانية بريجيت رويتر وسيقدم الفنان اضافة الى ذلك عملا تركيبيا ” انستليشن ” يتكون من اكثر من خمسين قطعة مخلفة الاشكال والحجوم والتقنيات : لوحات صغيرة , منحوتات , سيراميك , كولاج …الخ , وقد استعار الفنان عنوان العمل التركيبي ليكون عنوان للمعرض باسره ياءتي هذا المعرض , بعد معرضه الشخصي الذي افتتح منتتصف شهر تشرين الثاني نوفمبر , على فضاءات غاليري ” Frank Welkenhuysen ” بمدينة اوترخت و وكان بعنوان : ” الطريق الى بغداد ” والذي حظي بنجاح واهتمام ملحوظ يذكر ان على اجندة الفنان الساعدي العديد من المشاريع والمعارض التي ستستضيفها بعض الغاليريات والمتاحف في هولندا وبلجيكا والمملكة المتحدة . هذا ويتطلع الفنان الى اقامة معرضه الشخصي في وطنه العراق , ويصفه بالحلم الممكن والمستحيل لمزيد من المعلومات عن المعرض: |

Opening

Qassim Alsaedy met Brigitte Reuter (met wie hij samen het keramische werk maakte)

De Iraakse kunstenaars Wiedad Thamer, Salam Djaaz, Aras Kareem en Iman Ali

Qassim Alsaedy voor de camera van de Iraakse journalist Riyad Fartousi (zie filmpje helemaal onderaan dit bericht)

Qassims vrouw Nebal en dochter Urok

vlnr ikzelf, de Iraaks Koerdische journalist Goran Baba Ali (hoofdredacteur Ex Ponto), de Iraakse schrijver en journalist Riyad Fartousi, Qassim Alsaedy, Nebal Shamky (Qassims vrouw) en Ali Reza (onze Iraanse bovenbuurman)

De Iraaks Koerdische kunstenaar Aras Kareem (zie deze eerdere expositie), bij het werk van Qassim Alsaedy

Neil van der Linden, die de opening verrichtte

vlnr Goran Baba Ali, Herman Divendal (van AIDA), ikzelf, Riyad Fartousi, Qassim Alsaedy, Liesbeth Schreve, Scarlett Hooft Graafland en nog een bezoeker

interview met Qassim Alsaedy en Goran Baba Ali op de opening voor een Arabische zender (http://www.sutuur.com/ar/video)

Interview met Qassim Alsaedy door Entisar Al-Ghareeb

Voor de nieuwste ontwikkelingen, bekijk hieronder:

klik op bovenstaand logo

Gaddafi loses more Libyan cities |

Protesters wrest control of more cities as unrest sweeps African nation despite Muammar Gaddafi’s threat of crackdown.Last Modified: 23 Feb 2011 17:36 GMT

|

| Muammar Gaddafi, Libya’s long-standing ruler, has reportedly lost control of more cities as anti-government protests continue to sweep the African nation despite his threat of a brutal crackdown.Protesters in Misurata said on Wednesday they had wrested the western city from government control. In a statement on the internet, army officers stationed in the city pledged “total support for the protesters”.The protesters also seemed to be in control of much of the country’s east, and an Al Jazeera correspondent, reporting from the city of Tobruk, 140km from the Egyptian border, said there was no presence of security forces.”From what I’ve seen, I’d say the people of eastern Libya are the ones in control,” Hoda Abdel-Hamid, our correspondent, said.She said there were no officials manning the border when the Al Jazeera team crossed into Libya.‘People in charge’“All along the border, we didn’t see one policeman, we didn’t see one soldier and people here told us they [security forces] have all fled or are in hiding and that the people are now in charge, meaning all the way from the border, Tobruk, and then all the way up to Benghazi. |

|

“People tell me it’s also quite calm in Bayda and Benghazi. They do say, however, that ‘militias’ are roaming around, especially at night. They describe them as African men, they say they speak French so they think they’re from Chad.”

Major-General Suleiman Mahmoud, the commander of the armed forces in Tobruk, told Al Jazeera that the troops led by him had switched loyalties.

“We are on the side of the people,” he said. “I was with him [Gaddafi] in the past but the situation has changed – he’s a tyrant.”

Benghazi, Libya’s second largest city, was where people first rose up in revolt against Gaddafi’s 42-year long rule more than a week ago. The rebellion has since spread to other cities despite heavy-handed attempts by security forces to quell the unrest.

With authorities placing tight restrictions on the media, flow of news from Libya is at best patchy. But reports filtering out suggest at least 300 people have been killed in the violence.

But Franco Frattini, the Italian foreign minister, said there were “credible’ reports that at least 1,000 had died in the clampdown.

Defiant Gaddafi

Amid the turmoil, a defiant Gaddafi has vowed to quash the uprising.

He delivered a rambling speech on television on Tuesday night, declaring he would die a martyr in Libya, and threatening to purge opponents “house by house” and “inch by inch”.

He blamed the uprising in the country on “Islamists”, and warned that an “Islamic emirate” has already been set up in Bayda and Derna, where he threatened the use of extreme force.

| //

Jnoubiyeh The death toll keeps rising in #Libya. At least 500 Libyans are estimated to have been murdered by #Gaddafi since the uprising began. #Feb17 3 days ago · reply 700+ recent retweets NSlayton Saif #Gaddafi just blamed #Canada for chaos. I think that’s the first time someone’s blamed Canada for war outside of South Park. #libya 3 days ago · reply 1000+ recent retweets AJELive Al Jazeera receiving reports live ammunition being fired on protesters marching on #Gaddafi compound in Tripoli #Libya http://aje.me/fwtYjF 2 days ago · reply 100+ recent retweets |

He urged Libyans to take to the streets and show their support for their leader.

Several hundred government loyalists heeded his call in Tripoli, the capital, on Wednesday, staging a pro-Gaddafi rally in the city’s Green Square.

Fresh gunfire was reported in the capital on Wednesday, after Gaddafi called on his supporters to take back the streets from anti-government protesters.

But Gaddafi’s speech has done little to stem the steady stream of defections from his side.

Libyan diplomats across the world have either resigned in protest at the use of violence against citizens, or renounced Gaddafi’s leadership, saying that they stand with the protesters.

Late on Tuesday night, General Abdul-Fatah Younis, the country’s interior minister, became the latest government official to stand down, saying that he was resigning to support what he termed as the “February 17 revolution”.

He urged the Libyan army to join the people and their “legitimate demands”.

On Wednesday, Youssef Sawani, a senior aide to Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, one of Muammar Gaddafi’s sons, resigned from his post “to express dismay against violence”, Reuters reported.

Earlier, Mustapha Abdeljalil, the country’s justice minister, had resigned in protest at the “excessive use of violence” against protesters, and diplomat’s at Libya’s mission to the United Nations called on the Libyan army to help remove “the tyrant Muammar Gaddafi”.

A group of army officers has also issued a statement urging soldiers to “join the people” and remove Gaddafi from power.

http://english.aljazeera.net/news/africa/2011/02/201122445420412325.html

Gaddafi struggles to keep control |

|||||

Pro-democracy protesters take over eastern part of the country, as state structure appears to be disintegrating.Last Modified: 24 Feb 2011 12:15 GMT

|

|||||

Muammar Gaddafi, the Libyan leader, is struggling to maintain his authority in the country, as major swathes of territory in the east of the vast North African country now appear to be under the control of pro-democracy protesters.On Thursday, state television reported that he was due to make a public address to residents of Az Zawiyah, a town that saw fierce clashes between pro- and anti-government forces through the day.Ali, an eyewitness to the shooting, told Al Jazeera by phone that soldiers began shooting at the protesters with heavy artillery at around 6am and had continued for 5 hours.”They were trying to kill the people, not terrify them,” he said, explaining that the soldiers had aimed at the protesters’ head and chest.He estimated as many as 100 protesters had been killed. Approximately 400 people had been injured and were now in the town’s hospital. He said he had filmed the bodies after the shooting had stopped, but was unable to send the footage because internet access has been cut off.”The people here didn’t ask for anything, they just asked for a constitution and democracy and freedom, they didn’t want to shoot anyone,” he said.Gunfire could be heard in the background as Ali spoke, and he said the protesters were expecting the soldiers to launch another direct attack on Martyrs’ Square later in the evening.Despite the risk of more shooting, he said he and the other protesters would continue their protest, even if it cost their lives.Earlier, a Libyan army unit led by Gaddafi’s ally, Naji Shifsha, blasted the minaret of a mosque being occupied by protesters in Az Zawiyah, according to witnesses. They said that protesters had sustained , but exact figures remain unclear.

According to witnesses, pro-Gaddafi forces also attacked the town of Misrata, which was under the control of protesters. They told Al Jazeera that “revolutionaries had driven out the security forces”, who had used “heavy machine guns and anti-aircraft guns”. They said the pro-Gaddafi forces were called the “Hamza brigade”. Similar clashes have also been reported in the cities of Sabha in the south, and Sabratha, near Tripoli, which is in the west. Also on Thursday, anti-government protesters appeared to be in control of the country’s eastern coastline, running from the Egyptian border through to the cities of Tobruk and Benghazi, the country’s second largest city. Franco Frattini, the Italian foreign minister, said on Wednesday that protesters also held the city of Cyrenaica. Other towns that appear to no longer be under Gaddafi’s control include Derna and Bayda, among others across the country’s east. Reuters news agency, quoting Egyptian nationals fleeing the town of Zoura in the country’s west, reported that anti-government protesters had taken over the city. Ahmed Gadhaf al-Dam, one of Gaddafi’s top security official and a cousin, defected on Wednesday, saying in a statement issued by his Cairo office that he left the country “in protest and to show disagreement” with “grave violations to human rights and human and international laws”. Al-Dam was travelling to Syria from Cairo on a private plane, sources told Al Jazeera. He denied allegations that he was asked to recruit Egyptian tribes on the border to fight in Libya and said he went to Egypt in protest against his government’s used of violence. ‘People in control’ Soldiers in the cities controlled by the protesters have switched sides, filling the void and no longer supporting Gaddafi’s government. In a statement posted on the internet, army officers stationed in Misurata pledged their “total support” for the protesters. Major-General Suleiman Mahmoud, the commander of the armed forces in Tobruk, earlier told Al Jazeera that the troops led by him had switched loyalties. “We are on the side of the people,” he said. “I was with him [Gaddafi] in the past but the situation has changed – he’s a tyrant.” Thousands gathered in Tobruk to celebrate their taking of the city on Wednesday, with Gaddafi opponents waving flags of the old monarchy, honking cars and firing in the sky. “In 42 years, he turned Libya upside-down,” said Hossi, an anti-government protester there. “Here the leader is a devil. There is no one in the world like him.” Armed opponents of the government are also patrolling the highway that runs along the country’s Mediterranean coast. Al Jazeera’s correspondent said that even in the towns under anti-government forces’ control, gangs of pro-Gaddafi militias had been reported to be roaming the streets at night.

“From what I’ve seen, I’d say the people of eastern Libya are the one’s in control,” Hoda Abdel-Hamid, Al Jazeera’s correspondent who is in Libya, reported. She said that no Libyan officials had been manning the border where Al Jazeera’s team crossed into the country. Capital paralysed Tripoli, the Libyan capital, meanwhile, is said to be virtually locked down, and streets remained mostly deserted, even though Gaddafi had called for his supporters to come out in force on Wednesday and “cleanse” the country from the anti-government demonstrators. Libyan authorities said food supplies were available as “normal” in the shops and urged schools and public services to restore regular services, although economic activity and banks have been paralysed since Tuesday. London-based newspaper the Independent reported, however, that petrol and food prices in the capital have trebled as a result of serious shortages. Saif al-Islam Gaddafi, Muammar Gaddafi’s son, said on Thursday that an international investigation committee and media will be invited to tour Tripoli. During a tour of a state television channel, he emphasised that life was “normal” in the city.

On Wednesday, an army general told Al Jazeera that two pilots had ejected from their air force jet near the town of Agdabia after refusing to bomb civilians in Benghazi, which has been a stronghold of the anti-government protesters. In addition to desertions by many army troops, Gaddafi has also been faced with several diplomats in key posts, as well as cabinet ministers, refusing to recognise his authority and calling for him to be removed. Hundreds killed Foreign governments, meanwhile, continue to rush to evacuate their citizens, with thousands flooding to the country’s borders with Tunisia and Egypt. The United States, Britain, France, Italy, Turkey, China, France and India, among others, have made arrangements for their nationals to leave the country. James Bays, Al Jazeera’s correspondent, reported that there was “a desperate scene at Tripoli’s airport”. He said that there was a “log-jam” there, with some saying that they have been trying to leave the country for three days. “The airport is still very firmly under the control of Gaddafi’s people,” he reported, adding that secret police are patrolling the area, and several checkpoints have been set up on the road leading there. The Paris-based International Federation for Human Rights put the number of people killed at 640, though Nouri el-Mismari, a former protocol chief to Gaddafi, and Frattini, the Italian foreign minister, put the number closer to 1,000. Denying these figures as “fabrications,” the Libyan interior ministry on Wednesday said the death toll since the violence began is only 308 people. Since making statements against Gaddafi, el-Mismari’s lawyer has said that his daughters, who live in Libya, were “abducted … and forcibly taken to the [state] television [station] to deny their father’s statements”. |

|||||

http://english.aljazeera.net/news/africa/2011/02/2011224143054988104.html

Gaddafi blames unrest on al-Qaeda |

Libyan leader says protesters are young people being manipulated by al-Qaeda, as violence continues across the country.Last Modified: 24 Feb 2011 16:02 GMT

|

| Muammar Gaddafi, the Libyan leader, has said in a speech on Libyan state television that al-Qaeda is responsible for the uprising in Libya.”It is obvious now that this issue is run by al-Qaeda,” he said, speaking by phone from an unspecified location on Thursday.He said that the protesters were young people who were being manipulated by al-Qaeda’s Osama bin Laden, and that many were doing so under the influence of drugs.”No one above the age of 20 would actually take part in these events,” he said. “They are taking advantage of the young age of these people [to commit violent acts] because they are not legally liable!”At the same time, the leader warned that those behind the unrest would be prosecuted in the country’s courts. |

| LIVE BLOG |

|

He called on Libyan parents to keep their children at home.

“How can you justify such misbehaviour from people who live in good neighbourhoods?” he asked.

The situation in Libya was different to Egypt or Tunisia he said, arguing that unlike people in the neighbouring countries, Libyans have “no reason to complain whatsoever”.

Libyans had easy access to low interest loans and cheap daily commodities, he argued. The one reform he did hint might be possible was a raise in salaries.

‘Symbolic’ leader

Gaddafi argued that he was a purely “symbolic” leader with no real political power, comparing his role to that played by Queen Elizabeth II in England.

He also warned that the protests could cut off Libya oil production. “If [the protesters] do not go to work regularly, the flow of oil will stop,” he said.

Ibrahim Jibreel, a Libyan political activist, said that the fact that Gaddafi was speaking by phone showed that he did not have the courage to appear publically, and proved that he remained “under self-imposed house arrest in Tripoli”.

Jibreel said there were similarities between Thursday’s speech and one Gaddafi gave earlier in the week.

“The theme of people who have taken pills and hallucinations is one that continues to occur,” he said.

Jibreel noted Gaddafi’s reference to loans and that he would reconsider salaries. “I think that there [are] some concessions that he wants to make, in his own weird way,” he said.

Struggling

Gaddafi is struggling to maintain his authority in the country, as major swathes of territory in the east of the vast North African country now appear to be under the control of pro-democracy protesters.

|

| Follow more of Al Jazeera’s special coverage here |

Ali, an eyewitness to the shooting, told Al Jazeera by phone that soldiers began shooting at peaceful protesters on Martyrs’ Square with heavy artillery at around 6am and had continued for 5 hours.

“They were trying to kill the people, not terrify them,” he said, explaining that the soldiers had aimed at the protesters’ heads and chests.

He estimated as many as 100 protesters had been killed. Approximately 400 people had been injured and were now in the town’s hospital. He said he had filmed the bodies after the shooting had stopped, but was unable to send the footage because internet access has been cut off.

“The people here didn’t ask for anything, they just asked for a constitution and democracy and freedom, they didn’t want to shoot anyone,” he said.

Gunfire could be heard in the background as Ali spoke, and he said the protesters were expecting the soldiers to launch another direct attack on Martyrs’ Square later in the evening.

Despite the risk of more shooting, he said he and the other protesters would continue their protest, even if it cost their lives.

Mosque ‘attacked’

Also on Thursday, a Libyan army unit led by Gaddafi’s ally, Naji Shifsha, blasted the minaret of a mosque being occupied by protesters in Az Zawiyah, according to witnesses.

| //

libyafreedomnew Strong differences between Gaddafi’s sons … about the father prefers to Saif al-Islam and make it in the interface..#Libya #Gaddafi 5 minutes ago · reply NadeenR #Gaddafi has shares in #Juventus football club. Seriously. #LOL #Libya 4 minutes ago · reply nihonmama RT @libyafreedomnew: Resigned Libyan Justice Minister: There’s no presence for AlQaeda or any terroristic cells here. #Libya #Gaddafi 4 minutes ago · reply 6 new tweets DebateFaith – I bet Qaddafi and Pir Pagara have the same ancestors. #Pakistan #Libya: – I bet Qaddafi and Pi… http://bit.ly/h603oe #libya #gaddafi 5 minutes ago · reply DebateFaith RT @ChangeInLibya: Don’t put sanctions on #libya government. Impose a no fly zone ASAP and start… http://bit.ly/hT8z9v #libya #gaddafi 5 minutes ago · reply |

According to witnesses, pro-Gaddafi forces also attacked the town of Misrata, which was under the control of protesters.

They told Al Jazeera that “revolutionaries had driven out the security forces”, who had used “heavy machine guns and anti-aircraft guns”.

They said the pro-Gaddafi forces were called the “Hamza brigade”.

Similar clashes have also been reported in the cities of Sabha in the south, and Sabratha, near Tripoli, which is in the west.

Anti-government protesters appeared to be in control of the country’s eastern coastline, running from the Egyptian border through to the cities of Tobruk and Benghazi, the country’s second largest city.

Ahmed Gadhaf al-Dam, one of Gaddafi’s top security official and a cousin, defected on Wednesday evening, saying in a statement issued by his Cairo office that he left the country “in protest and to show disagreement” with “grave violations to human rights and human and international laws”.

Al-Dam was travelling to Syria from Cairo on a private plane, sources told Al Jazeera. He denied allegations that he was asked to recruit Egyptian tribes on the border to fight in Libya and said he went to Egypt in protest against his government’s used of violence.

Communications blocked

Libyan authorities are working hard to prevent news of the events in the country from reaching the outside world.

Thuraya, a satellite phone provider based in the United Arab Emirates, has faced continuous “deliberate inference” to its services in Libya, the company’s CEO told Al Jazeera.

Samer Halawi, the company’s CEO, said his company will be taking legal action against the Libyan authorities for the jamming of its satellite.

“This is unlawful and this in uncalled for,” he said.

The company’s engineers have had some success in combating the jamming, and operations were back on almost 70 per cent of the Libyan territory on Thursday, Halawi said. The blocking was coming from a location in Tripoli.

The Libyan government has blocked landline and wireless communications, to varying degrees, in recent days.

Some phone services were down again on Thursday. In the town of Az Zawiyah, phone lines were working but internet access was blocked.

Nazanine Moshri, reporting from the northern side of the Tunisian-Libyan border near the town of Ras Ajdir, said that security forces were confiscating cellphones and cameras from people crossing into Tunisia.

“The most important thing to them is to not allow any footage to get across the border into Tunisia,” she reported.

Capital paralysed

Tripoli, the Libyan capital, meanwhile, is said to be virtually locked down, and streets remained mostly deserted, even though Gaddafi had called for his supporters to come out in force on Wednesday and “cleanse” the country from the anti-government demonstrators.

Libyan authorities said food supplies were available as “normal” in the shops and urged schools and public services to restore regular services, although economic activity and banks have been paralysed since Tuesday.

London-based newspaper the Independentreported, however, that petrol and food prices in the capital have trebled as a result of serious shortages.

Foreign governments, meanwhile, continue to rush to evacuate their citizens, with thousands flooding to the country’s borders with Tunisia and Egypt.

http://english.aljazeera.net/news/africa/2011/02/2011225165641323716.html

Gaddafi addresses crowd in Tripoli |

|||||

Libyan leader speaks to supporters in the capital’s Green Square, saying he will arm people against protesters.Last Modified: 25 Feb 2011 18:00 GMT

|

|||||

Muammar Gaddafi, the Libyan leader, has appeared in Tripoli’s Green Square, to address a crowd of his supporters in the capital.”We can defeat any aggression if necessary and arm the people,” Gaddafi said, in footage that was aired on Libyan state television on Friday.”I am in the middle of the people.. we will fight … we will defeat them if they want … we will defeat any foreign aggression.

“Dance … sing and get ready … this is the spirit … this is much better than the lies of the Arab propaganda,” he said. The speech, which also referred to Libya’s war of independence with Italy, appeared to be aimed at rallying what remains of his support base, with specific reference to the country’s youth. His last speech, on Thursday evening had been made by phone, leading to speculation about his physical condition. The footage aired on Friday, however, showed the leader standing above the square, waving his fist as he spoke. Tarik Yousef, a senior fellow at the Brookings Institute in Washington, told Al Jazeera that most of the individuals on Green Square are genuine Gaddafi supporters. “Most of these people have known nothing else but Gaddafi. They don’t know any other leader. And many of them stand to lose when Gaddafi falls,” Yousef said. “I am not completely surprised that they still think that he is the right man for Libya. What is striking is that [Gaddafi] did not talk about all the liberated cities in his country. “This was a speech intended show his defiance and to rally against what he calls foreign interference. But even his children have admitted that the east of the country is no longer under the regime’s control.” Anti-Gaddafi protesters shot Gaddafi’s speech came on a day when tens of thousands of Libyans in the capital and elsewhere in the country took to the streets calling for an end to his rule. As demonstrations began in Tripoli following the midday prayer, security forces loyal to Gaddafi reportedly began firing on them. There was heavy gun fire in various Tripoli districts including Fashloum, Ashour, Jumhouria and Souq Al, sources told Al Jazeera. “The security forces fired indiscriminately on the demonstrators,” said a resident of one of the capital’s eastern suburbs. “There were deaths in the streets of Sug al-Jomaa,” the resident said. The death toll since the violence began remains unclear, though on Thursday Francois Zimeray, France’s top human rights official, said it could be as high as 2,000 people killed. Dissent reaches mosques Violence flared up even before the Friday sermons were over, according to a source in Tripoli. “People are rushing out of mosques even before Friday prayers are finished because the state-written sermons were not acceptable, and made them even more angry,” the source said. Libyan state television aired one such sermon on Friday, in an apparent warning to protesters. “As the Prophet said, if you dislike your ruler or his behaviour, you should not raise your sword against him, but be patient, for those who disobey the rulers will die as infidels,” the speaker told his congregation in Tripoli. During Friday prayers a cleric in the town of Mselata, 80km to the east of Tripoli, called for the people to fight back. Immediately after the prayers, more than more than 2,000 people, some of them armed with rifles taken from the security forces, headed towards Tripol to demand the fall of Gaddafi, Al Jazeera’s Nazanine Moshiri reported. The group made it as far as the city of Tajoura, where it was stopped by a group loyal to Gaddafi. They were checked by foreign, French-speaking mercenaries and gunfire was exchanged. There were an unknown number of casualties, Moshiri reported, based on information from witnesses who had reached on the Libyan-Tunisian border. Special forces People in eastern parts of the country, a region believed to be largely free from Gaddafi’s control, held protests in support for the demonstrations in the capital. “Friday prayer in Benghazi have seen thousands and thousands on the streets. All the banners are for the benefit of the capital, [they are saying] ‘We’re with you, Tripoli.'” Al Jazeera’s Laurence Lee reported. In the town of Derna, protesters held banners with the messages such as “We are one Tribe called Libya, our only capital is Tripoli, we want freedom of speech”. Al Jazeera’s correspondent in Libya reported on Friday that army commanders in the east who had renounced Gaddafi’s leadership had told her that military commanders in the country’s west were beginning to turn against him. They warned, however, that the Khamis Brigade, an army special forces brigade that is loyal to the Gaddafi family and is equipped with sophisticated weaponry, is currently still fighting anti-government forces. The correspondent, who cannot be named for security reasons, said that despite the gains, people are anxious about what Gaddafi might do next, and the fact that his loyalists were still at large. “People do say that they have broken the fear factor, that they have made huge territorial gains,” she said. “[Yet] there’s no real celebration or euphoria that the job has been done.” Pro-democracy protesters attacked On Friday morning, our correspondents reported that the town of Zuwarah was, according to witnesses, abandoned by security forces and completely in the hands of anti-Gaddafi protesters. Checkpoints in the country’s west on roads leading to the Tunisian border, however, were still being controlled by Gaddafi loyalists. In the east, similar checkpoints were manned by anti-Gaddafi forces, who had set up a “humanitarian aid corridor” as well as a communications corridor to the Egyptian border, our correspondent reported.

Thousands massed in Az Zawiyah’s Martyr’s Square after the attack, calling on Gaddafi to leave office, and on Friday morning, explosions were heard in the city. Witnesses say pro-Gaddafi forces were blowing up arms caches, in order to prevent anti-government forces from acquiring those weapons. Clashes were also reported in the city of Misurata, located 200km east of Tripoli, where witnesses said a pro-Gaddafi army brigade attacked the city’s airport with mortars and rocket-propelled grenades. They told Al Jazeera that pro-democracy protesters had managed to fight off that attack. “Revolutionaries have driven out the security forces,” they said, adding that “heavy machine guns and anti-aircraft guns” had been used against them. Mohamed Senussi, a resident of Misurata, said calm had returned to the city after the “fierce battle” near the airport. “The people’s spirits here are high, they are celebrating and chanting ‘God is Greatest’,” he told the Reuters news agency by telephone. Another witness warned, however, that protesters in Misurata felt “isolated” as they were surrounded by nearby towns still in Gaddafi’s control. Government loses oil terminals

Protesters and air force personnel who have renounced Gaddafi’s leadership also overwhelmed a nearby military base where Gaddafi loyalists were taking refuge, according to a medical official at the base. They disabled air force fighter jets at the base so that they could not be used against protesters. Soldiers helped anti-Gaddafi protesters take the oil terminal in the town of Berga, according to Reuters. The oil refinery in Ras Lanuf has also halted its operations and most staff has left, according to a source in the company. Support for Gaddafi within the country’s elite continues to decline. On Friday, Abdel Rahman Al Abar, Libya’s Chief Prosecutor, became one of the latest top officials to resign in protest over the bloodshed. “What happened and is happening are massacres and bloodshed never witnessed by the Libyan people. The logic of power and violence is being imposed instead of seeking democratic, free, and mutual dialogue,” he said. His comments came as UN’s highest human-rights body held a special session on Friday to discuss what it’s chief had earlier described as possible “crimes against humanity” by the Gaddafi government. Navi Pillay, the UN High Commissioner on Human Rights, urged world leaders to “step in vigorously” to end the violent crackdown. The United Nations Security Council was to hold a meeting on the situation in Libya later in the day, with sanctions the possible imposition of a no-fly zone over the country under Chapter VII of the UN charter on the table. |

|||||

|

Source:

Al Jazeera and agencies

|

|||||

http://english.aljazeera.net/indepth/features/2011/02/201121310169828350.html

Anti-terrorism and uprisings |

||||||

North African leaders have worked with the West against Islamists and migrants – becoming more repressive as a result.Yasmine Ryan Last Modified: 25 Feb 2011 17:47 GMT

|

||||||